Thoughts on Education – 3/28/2012 – Thinking about the future of education

I haven’t done any article reviews in a while, so I thought I’d sit down and hit my Evernote box a bit here. So, here we go.

The first article comes from the ProfHacker blog at the Chronicle of Higher Ed. As with so many others, the intent here is to look at way the future of the university system will be, and while I teach at a community college, and not a university, the ideas are still relevant. I also, of course, like the origin of this one, since it came out of a conference at my alma mater, Rice University. It starts off this way: “I sometimes hear that the classroom of today looks and functions much like the classroom of the 19th century—desks lined up in neat rows, facing the central authority of the teacher and a chalkboard (or, for a contemporary twist, a whiteboard or screen.) Is this model, born of the industrial age, the best way to meet the educational challenges of the future? What do we see as the college classroom of the future: a studio? a reconfigurable space with flexible seating and no center stage? virtual collaborative spaces, with learners connected via their own devices?” Certainly, my classrooms are set up that way, even my “other” classroom, the two-way video one, still has all of the emphasis on me. The article also noted: “With declining state support, tuition costs are rising, placing a college education further out of reach for many people. Amy Gutmann presented figures showing that wealthy students are vastly over-represented at elite institutions even when controlling for qualifications. According to Rawlings, higher education is now perceived as a “private interest” rather than a public good. With mounting economic pressures, the public views the purpose of college as career preparation rather than as shaping educated citizens. In addition, studies such as Academically Adrift have raised concerns that students don’t learn much in college.” I have posted up articles that talk about both of those things before, but this information from this conference really narrows it all down well. At its heart, what the article notes from the conference is that it is time to update the model to the Digital Age from our older Industrial Age. That we have adopted the multiple-choice exam and the emphasis on paying attention in class from this old Industrial model, where creating a standardized and regulated labor force was key. In the Digital Age, it will be important to “ensure that kids know how to code (and thus understand how technical systems work), enable students to take control of their own learning (such as by helping to design the syllabus and to lead the class), and devise more nuanced, flexible, peer-driven assessments.” Throughout the conference, apparently, the emphasis was on “hacking” education, overturning our assumptions, and trying something new. While the solutions are general in nature, I found this summary of the conference to be right up my alley, and certainly a part of my own thinking as I redesign. I wish I had known about the conference, as I would have loved to have attended.

Looking at the question from the opposite end is this article from The Choice blog at The New York Times. The blog post was in response to the UnCollege movement, that says that college is not a place where real learning occurs and that students would be better off not going to college and just going out and pursuing their own dreams and desires without the burden of a college education. What is presented here is some of the responses to that idea. A number of people wrote in talking about what the value of college is, so this gives some good baseline information on what college is seen as valuable for. Here are some of them:

- “a college degree is economically valuable”

- “college is a fertile environment for developing critical reasoning skills”

- several noted that you can get a self-directed, practical college education if you want it

- “opting out is generally not realistic or responsible, given the market value of a degree”

- “the true value of college is ineffable and ‘deeply personal,’ not fully measurable in quantifiable ways like test scores and salaries”

That’s just some of the responses, specifically the positive ones, as that’s what I’m looking at here. It is interesting to see the mix of practical things and more esoteric ideas. I think that both are hopefully a part of college education and that both are part of what we deliver. I would like to think that’s what my students are getting out of college in general, and I hope that the redesign that I am going for will help foster that even more. I especially hope to bring more of the second and fifth comments into what I am doing, as that is the side that I think a college history class can help with.

Then there is this rather disturbing article, again from The Chronicle of Higher Ed. It discusses the rising push for more and more online courses, especially at the community college level. As the article notes, that is often at the center of the debate over how to grant a higher level of access to the education experience for more and more people. But, with more emphasis being put on the graduation or completion end and less on the how many are enrolled end, this could end up putting community colleges at an even higher disadvantage. As one recent study put it, “‘Regardless of their initial level of preparation … students were more likely to fail or withdraw from online courses than from face-to-face courses. In addition, students who took online coursework in early semesters were slightly less likely to return to school in subsequent semesters, and students who took a higher proportion of credits online were slightly less likely to attain an educational award or transfer to a four-year institution.'” So, we are actually putting our students into more online classes that make them less likely to finish overall. In fact, they are not only less likely to finish, but they are less likely to succeed at that specific class or come back for later classes. As well, a different study pointed out similar problems for online students: “‘While advocates argue that online learning is a promising means to increase access to college and to improve student progression through higher-education programs, the Department of Education report does not present evidence that fully online delivery produces superior learning outcomes for typical college courses, particularly among low-income and academically underprepared students. Indeed some evidence beyond the meta-analysis suggests that, without additional supports, online learning may even undercut progression among low-income and academically underprepared students.'” This is disturbing to me, as this is exactly what I teach at least half of my schedule each semester in – the online environment exclusively. I know that success in an online class is difficult, although I have actually been slowly improving the success rate over time in my online sections. I think I’ve finally hit a good sweet spot with the online classes right now, and I’m less in need of fixing them at the moment. I do, however, agree with the very end of the article that says that what is often missing from the online courses is the “personal touch.” That is the only part of the class that I would like to change, as I need a way for me to be more active in the class right now. I can direct from the point of putting in Announcements and the like, but I do feel that I get lost in whatever the day to day activities are. I need to design some part of the class that has me participating more directly rather than leaving it up to the students. Otherwise, I do think I’m doing pretty well in this part of my teaching career.

OK. I think I’m going to call it a night here. Any reactions?

Thoughts on Education – 3/22/2102 – My first webinar

So, I had the opportunity on Tuesday to lead my first webinar. It is not something that I have done before, and it was an interesting new experience. I was working with McGraw-Hill for this one, helping them demonstrate Connect History to faculty members around the US. I can’t say we had a huge turnout, as there were only 4 faculty members on the webinar, although we had about twice as many McGraw-Hill employees there as well. My job was to talk for about 20 minutes and demonstrate how I use the Connect History platform. I was sharing my desktop in the process, so that the people there could see what I do with Connect History in my classroom. Then, I took questions for the rest of the time. As I said above, it was an interesting experience. I have participated in webinars before, but it was my first time leading one. It was not a particularly difficult thing to do, as it naturally feeds from the experience that we have as instructors anyway. It is just a different thing, as you are there with no direct audience, talking to a computer screen without being able to see anyone else. I do feel that I effectively communicated what I was supposed to, and I think the participants were satisfied (all except one who would never be satisfied, from what I can tell).

In a broader sense, the webinar format certainly makes me think about delivery of material online in general. I can’t help but think that some format like this would be great for an online course. The only problem is that it really does require everyone to be on at the same time to get the basic interaction down. Otherwise, you are just working with a static delivery of material anyway. If you could commit your students to being online all at a certain time to hear you lecture or discuss, you could do a lot and not take up classroom space at the same time. It is an interesting idea, scheduling an online course to take place at a certain time, even well outside the normal times that we would meet face-to-face. Certainly this does not get me past the lecture, as I have been talking about here, but I can’t help but see a more personalized experience like this being much better than the required time that a student has to come and sit in class. Of course, I would still be requiring the students to be there at a certain time anyway. I wonder about a running discussion or something like that, where students could come and go over the course of hours, and I would just be there to moderate and guide for that time. I wonder if that would be more effective that the old standby of a discussion forum.

What do you think? Have you taken any webinars? What do you think of the format? Could we do something like this as teachers and enhance/change the online experience?

Thoughts on Education – 3/20/2012 – A long article

I promised that I would return to this article, and so I will here. I had read it earlier and just revisited it now. I was quite impressed with the thought that went into the article, and I found myself agreeing with a lot of what he said. I especially liked these ideas here:

- “Instructors walk to the front of rooms, large and small, assuming that their charges have come to class “prepared,” i.e. having done the reading that’s been assigned to them — occasionally online, but usually in hard copy of some kind. Some may actually have done that reading. And some may actually do it, after a fashion, before the next paper or exam (even though, as often as not, they will attempt to get by without having done so fully or at all). But the majority? On any given day?”

- “We want them to see the relevance of history in their own lives, even as we want them to understand and respect the pastness of the past. We want them to evaluate sources in terms of the information they reveal, the credibility they have or lack, or the questions they prompt. We want them to become independent-minded people capable of striking out on their own. In essence, we want for them what all teachers want: citizens who know how to read, write, and think.”

- “We think it’s our job to ask students to think like historians (historians, who, for the moment, were all born and trained in the twentieth century). We don’t really consider it our job to think like students as a means of showing them why someone would want to think like a historian. We take that for granted because it’s the choicewe made. Big mistake.”

- “For one thing, there’s too much “material” to “cover” (as if history must — can — be taught sequentially, or as if what’s covered in a lecture or a night’s reading is likely to be remembered beyond those eight magic words a student always longs to to be told: “what we need to know for the test”). For another, few teachers are trained and/or given time to develop curriculum beyond a specific departmental, school, or government mandate. The idea that educators would break with a core model of information delivery that dates back beyond the time of Horace Mann, and that the stuff of history would consist of improvisation, group work, and telling stories with sounds or pictures: we’ve entered a realm of fantasy (or, as far as some traditionalists may be concerned, a nightmare). College teachers in particular may well think of such an approach as beneath them: they’re scholars, not performers.”

- “Already, so much of history education, from middle school through college, is a matter of going through the motions.”

- “Can you be a student of history without reading? Yes, because it happens every day. Can you be a serious student of history, can you do history at the varsity level, without it? Probably not. But you can’t get from one to the other without recognizing, and acting, on the reality of student life as it is currently lived. That means imagining a world without books — broadly construed — as a means toward preventing their disappearance.”

OK, so if you’ve stuck with me this far, you are looking for more than just a bland repeating of what someone else said. So, here are my own thoughts on the matter. I think this is spot on with regard to the assumptions that we make in teaching history. I have long since given up on the idea that my students actually do the reading that I assign, although I do my damnedest to get them to. I put together more and more complex quizzes that the students have to complete on each chapter, with the hope that they will not be able to complete them without reading the chapters. Actually, I won’t even say I do that, as more of the approach I make is that it will be much easier and faster for the students to complete the assignments they are required to do if they have actually done the reading. What is funny, and really a failing on my part, is that I still run the class as if they are doing the reading, even though I know they don’t. This is exactly the fault at which this article is aimed.

I also fall victim to the idea of coverage. I feel that, as long as I am lecturing, then I am expected to fully cover the material for the course, telling the students everything that they are supposed to know. I adopt that “sage on the stage” persona so easily that it is scary. All it takes is for me to stand up in front of the class, and I can talk for 75-minutes on the subject, never asking questions, never stopping for clarifications, and just going, going, going. I do that day after day without really trying. Despite my best intentions, I have the standard lecture class down pat, so much so that it takes very little preparation on my part these days to be able to walk in and deliver that lecture. I wish this wasn’t so, but I feel that I’ve actually gotten lazy with my teaching, just delivering the same old series of lectures, which are now on their 4th year since the last set of revisions. I’m no better than that joke that we all laugh about of the old professor going in with his old hand-written notes on a legal pad that he did 20 years earlier and delivering the same lecture. I have fallen into that trap. Instead of innovating in the place where it matters most, I am stagnating. I have innovated everywhere else, but day in and day out, I do the same old thing.

So, what can I do? Well, I have already been planning it out in this blog, and the more I read things like this article, the more I am convinced that it is time for a radical change. I don’t mean incremental change with some modifications to the lecture and so forth. I mean radical change. Blowing up the lecture class. Flipping the classroom. Whatever you want to call it. I need to approach the students and deliver to them, not do what I and my colleagues have always done. And when I step down from my teaching high each day, I look around at the students, and what do I see? They are gazing off into the distance, texting on their phones, watching me, surfing the internet, taking notes, dozing, and all sorts of things. Yet, all of those things are passive. Sitting there. Letting themselves either be entertained or annoyed at having to be there (as if I’m forcing them to get a college education). I want an active classroom. I want the students to be engaged. I want to teach history, historical thinking, critical thinking, and so much more. I don’t want to just lecture, deliver. To do that, I’m going to have to step out of my comfort zone. I’m going to have to stop going in with my pre-made lecture and talk for 75 minutes. I will have to do it all differently. I will have to change. It will be hard. It will be a lot of work. It will be uncertain. But I hope it will also be valuable to my students and to me.

Thoughts on Education – 3/15/2012 – What is college for?

I can’t help but start today with a response to an article that I discussed in my last education post. The original article had students talking about what they didn’t like about the lecture format. This one has professors responding. I will be honest that the professor responses are quite underwhelming in my opinion. I don’t know if it is a result of editing that makes the professors less compelling than the students or what. In fact, the best response that I saw there was in the form of a PowerPoint, but the editing of the video made it impossible to read the PowerPoint fully in the time allotted for it. However, when paused, the best points are there, and they largely mirror the ones that I would make. That is, the the failure of lecture is the fault of both the instructor and the student. Since the fault of the instructor has already been raised, I’ll focus on the student side. Students are raised in our educational culture to see education as both something they will be guaranteed basic success at with not that much effort and as something that is a nuisance and waste of time. That combined attitude is hard to combat in a semester course, when the student is one of many sitting out there in a semester class. As well, when they get to college, most students have not encountered the straight-up lecture format before, and it is simply foreign. As the PowerPoint points out, the students are encountering a different form of education for the first time, and they are being asked to adapt to it. However, our current educational structure is so student-focused that the students are not expected to adapt anymore. They should be catered to completely and not asked to leave their comfort zone. When the students encounter the lecture format for the first time in college, they have gone through a life of having their own educational styles catered to over and over, and so their reaction to the lecture is what you would expect. They want what they want, not what we want. What is interesting about this is that I will repeatedly stand up for the right of myself and fellow instructors to grade differently (usually harder) and assess differently, but I am willing to explore different methods of content delivery because the students aren’t responding. I wonder why this is. I have made my own comments here about the lecture format, and I guess that’s it. I do agree that the lecture format is broken, so I have much more tolerance for trying something new.

Of course, what all of this leads into is the bigger question of what college is for. A couple of articles have passed through my Evernote on this topic as well recently. It always helps when the current presidential candidates are talking about it, as that leads to a number of related articles scattered throughout the news sphere. This one from The Washington Post tries to address this broad issue. I have been reading Michelle Singletary’s commentary on personal finance for a while, so I would have read this one even without the educational focus. She sets up the standard two sides of education here, asking, “Is college a time for young adults to just enrich their minds, or should students use that time to concentrate on a major that will prepare them for a career?” She comes solidly down on the second motivation, pretty much dismissing the idea that college should be a time to take whatever classes you want, get whatever degree you want, and just explore. Her point is primarily financial, which makes sense as she is a financial correspondent. She believes that the financial cost of education these days means that students do not have the ability to learn for the sake of learning and need to be focused on what they can get for their education. She does not completely dismiss the idea of education for education’s sake, but she definitely comes down on the side of a practical education. I can’t say I disagree, but I certainly did the opposite. I don’t think I ever got a practical degree, and I feel lucky to have looked for a job and gotten one with my MA in History just before the recent financial collapse. My wife is just finishing up a BA in Art History, and we are currently trying to figure out what to do with that. So, I can understand. It is also at the root of why so many of my students ask me what they have to take history, as they see no practical use for it.

I just have to note this article from The Washington Post as well. It is from the Class Struggle blog on their site, and it gives a nice historical look at the idea of college. As Jay Matthews notes, “The outpouring of college student support after World War II fueled the unprecedented surge of the U.S. economy and its education system. This would be a good time to remember that before we start slipping back.” He notes the challenges facing the idea of college education all around, with Obama pushing more students to enter college, while Santorum is saying we should not. Matthews points out that we see a similar discrediting of education for all that was also seen just before the big push from the GI Bill. He warns us to remember that the benefits of education always seem to vastly outweigh the cost. I am never explicit about this when I teach my students directly. I do, however, always try to talk about the idea of education to my students and to place the education they are getting into a broader context for them. I hope that I do that reasonably well, but I know I could do more. I wonder at what level I need to be doing something like this, talking more about college in the historical sense. I know that the students generally don’t get much direct discussion of the value of college, so we would probably do well to talk ourselves up.

I’m going to close here, as the next article I want to talk about probably needs its own post. Just as a preview, this is the article I want to discuss in some detail. Your homework – read it ahead. OK, just kidding, but it is quite interesting.

Thoughts on Education – 3/11/2012 – What is broken in higher education?

I’ve taken some time off as we begin Spring Break here to get some of my own stuff done. We are doing a big clean out around the apartment, as we are probably going to move out of out apartment when our lease is up, and it would be nice to move a lot less stuff. I also sat down to start our taxes this weekend. Other than that, I’ve been trying to do “other” things, such as catching up on magazine/free reading, going through paperwork, and such things like that.

On my plate also is catching up on some of the articles I’ve been saving up. I’m trying to group them into themes, and today’s theme is articles that talk about what’s wrong with higher education today. I’m going to hold off on my own opinion here to open this post, as that will come out as we move along here.

The first article I came across is this one from the Chronicle of Higher Education. At its center is a YouTube video that talks about why students think that the lecture is a failing model for education. Three big points that come out of it, I think:

- First, they talk about lectures being boring, especially those where the professor simply reads off of the PowerPoint. This is undeniably true, and not just for students. I have been to enough conferences and presentations where this same thing was done to have experienced it myself many times. Solution? Well, we certainly could use some training for how to teach/lecture. Also, professors just need to care more. If that’s what they are doing, then it’s hard to call that really teaching. I imagine, however, that a lot of this is exaggeration on the part of students as well, as I know there are many students who would be dissatisfied/bored with anything that they were told they had to do, which would include listen to a lecture.

- Second, a comment that resonates with me is the one about attention spans and the 90-minute class. While we don’t have 90-minute classes at my community college, we certainly have mostly 75-minute classes. When the average human attention span is 20-25 minutes at the outside, we are asking even the best and most dedicated students to do something unreasonable if we expect them to sit and pay attention to a lecture for 75 minutes at a time. Yet, I do that very thing every day I’m in class.

- Third, and really the comment that stood out to me the most, one students said that they are told over and over to think outside the box, yet the ones who never seem to innovate are their own professors in their teaching styles. Yup. Can’t say anything more than that is spot on.

A second interesting article also addresses these concerns. In “Why School Should be Funnier,” Mark Phillips discusses the uses of humor in the classroom. I think that we do too often take the view that classes and college are serious, important things. As he says in the article, he’s not talking about throwing in a few jokes but about really seeing the absurdity of the situation we are put in. I address this regularly with my class, as I am very open about the failures of the lecture model and how the fact that they are expected to sit here and pay attention for all this time through the semester is, to a certain extent, absurd. My students (I hope!) appreciate it when I give the sly asides, the knowing winks, the “real reason you need to know this,” and all of the other things that I try to do to keep them engaged and going in a format that encourages torpor and boredom.

A third article focuses on the problems of who is driving educational reform. In this case, the experts are pulling us forward to the future. Educational reformers rely on educational experts to tell them what they should do to fix things. Usually, these experts are located outside of schools, connected with specific political ideas, and intent on fixing one part of the system at a time. In each of these cases, we end up with a failure of reform. I have not been asked much about what I think works or not, that’s for sure. In fact, the one group that usually does ask me what works or not are the textbook publishers. I hear from multiple publishers all the time who want me to tell them what is working and what doesn’t. Yet, as you move up the chain of administration or outside of my college completely, I have yet to have any input on the reforms coming down to me. It does always blow my mind every time I see the next thing coming through, and I have to wonder who thought that up. Perhaps we need a revolution from below to fix things.

To close today (yeah, I know, not a long one today, but I am on vacation . . .) is an article about the path of college from The Huffington Post. In it, the author brings together multiple different studies to talk about something very important when considering what is broken in higher education. At the heart of it, we still have an assumption that college works as a straight line, where you graduate from high school, pick a college, go to it, and graduate in four years. Even at a community college, we look at that same thing as the norm, with just the detour of a community college first. I must admit, that is exactly what I assume still as well, despite the evidence in front of my face every day. The reality is that students start, stop, transfer around, switch degrees, leave for 15 years, have kids, hold multiple jobs, get sick, take care of sick family members, join the military, drop out, etc. To shove everyone into that little box of four-year completers is just stupid, when you get right down to it. And, our funding at the college level is dependent on that completely. We fail a student if we can’t get them out in 2 years for community college and 4 years for college. Yet, how many people really do that? How many want to do that? Our funding levels depend on a myth of college completion. Our assumptions about how to teach and advise students works on this myth. Our assumptions on who a student is and what he or she should do in our classes rests on this myth. What is broken is the way we do things. What needs to be fixed is the way we do things. While it is easy to blame the students for that whole list of things that I said up there, the reality is that the students are going to be that no matter what. We have to figure out how to adapt to it. And the people who give us the money to be able to do this had better get it in their heads that just because we can’t say that 100% of our students graduated from our community college in 2 years, that does not mean that we are failing.

Thoughts on Education – 3/9/2012 – Using technology in the classroom

I’m going to try and get back to some of the education issues that have been coming through my Evernote lately. I’ve got quite a backlog over the last couple of weeks while I have been grading, so I should have plenty to write about over the next week or so. Today, I want to concentrate in on the general category of technology in the classroom, as I have been accumulating quite a bit on that recently. Of course, the recent Apple announcements and developments are relevant to this as well.

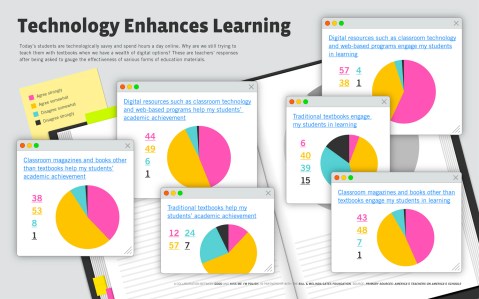

I’m going to start here, with a general article about what teachers think in general about the use of technology. As the article itself says, the results are not particularly surprising, but I will put up the general infographic here, as it illustrates what I think is not too far off from what I see, especially among the younger faculty.

I hope that you can click on that to make it bigger, but the basic message here is that the majority of teachers surveyed thought that technology in the classroom would help both the learning of the students and their engagement with the material. In fact, the two questions that refer back to the older “technology,” namely textbooks, got the lowest Agree responses and the highest Disagree responses. Again, I don’t think there is anything surprising at all about this, but I wanted to start here.

In a similar vein is this article from The Washington Post, which discusses how textbooks are failing to engage our students and help them learn. He notes that textbooks are not effective at engaging students because that is not what sells textbooks. We don’t choose a textbook (me included) because I think it is going to be some sort of magical panacea to solve all of the problems for my students. Instead, at least in history, we look at them primarily in terms of coverage. Which textbook covers the material we want to cover is more important than which textbook students will like. In fact, I have often found that if you talk to a group of instructors about choosing textbooks, the textbook that is most likely to be appealing to students is often dismissed out of hand as not being what works for us as instructors. So, there is a fundamental disconnect there. My feeling about this is echoed in the article as well, where one teacher is quoted as saying, “Even when adoption committees include content specialists, these people typically evaluate the accuracy of the content, rather than whether the instructional strategies are effective.” In fact, the author quotes another educational administrator, who noted, “The educational community was quick to respond to the (legitimate) criticism of textbooks but quicker still to adopt their horrific replacements: excessive use of lecture, worksheets, movies, poster making, and pointless group work.” We are flailing around as far as I can see. I feel like that myself, where I am just trying so many different things all the time without ever knowing what I’m doing. That’s why I’m doing this, so that instead of trying new things at random, I am trying to plan things out. Anyway, there’s a lot more to this article, and I do recommend it as very interesting reading when we think about how the old technology options are failing us.

And, when I read this article from the Chronicle, I saw myself and how I use technology a lot of times. Unfortunately, I don’t mean that in a good way. As it says, in online courses, especially at the community college level, “the professors are relying on static course materials that aren’t likely to motivate students or encourage them to interact with each other.” While I get a lot of compliments from students about the way my course is organized, I know that I use few real tools, and I certainly do not effectively encourage interaction in my classes. The article goes on to talk about a study where the results came from. That study concluded: “It found that most professors relied on text-based assignments and materials. In the instances when professors did decide to use interactive tools like online video, many of those technologies were not connected to learning objectives, the study found.” I certainly would say mine fits this completely. My course, is completely text-based. There is little to no video or interaction in my own materials. I have adopted some from McGraw-Hill that I use in conjunction with my textbook, but that is actually in a completely separate classroom from my own in Moodle. While the article does note that technology is again not a panacea to solve all of these problems, I think that in the online environment, a failure to be innovative in technology will cause the students to treat the course as a chore to get through. Of course, I may just be thinking some fairy-tale thoughts here that a student could really feel completely engaged by an online course, but I think I could do better.

As we think about the future of technology in the classroom, there are a lot of directions it could go. I’ve been exploring some of those in this blog as I have gone on here. I am trying to keep current on what’s going on out there, and trying to see what ideas might work for me. This article from Mind/Shift talks about the future of technology in the classroom. The article considers the near, medium, and long term forecast for technology. In the near term they consider mobile apps and tablet computing as the center piece of where we are going. We certainly are thinking about that at my community college. The faculty work group that I’m on has been given iPads to explore and the task of finding apps that can be used in the classroom to enhance learning. As well, we will be buying classroom sets of iPads to use. So, nothing new there based on what I have seen. The mid term is going to be gamification and the use of data to influence education. I have also been exploring gamification in this blog, so I guess I’m right on top of that topic as well. As to the use of data, if the big assessment push we all seem to be on is any indication, I think we’re already on this path. I don’t know how far it will go, but it is certainly a trend that we are involved in. The longer term is going to include gesture-based computing and increasingly ubiquitous connections to everything. I certainly agree that those are both technologies that could come into play. What is interesting about the article though is that the so-called future of technology in education includes little that I’m not already engaged with. I guess that means that instead of looking to these things to come out in the future, I need to figure out how to use them now and just get on with it.

So, where am I going with this. Still thinking, but moving along. I want to incorporate technology, and I want relevant change. I don’t want change for the sake of change, as I feel like that is what I have been doing for quite a while here. I think that more is needed, which is why I keep working on this blog. I need real change that comes with solid thought and evidence behind it. It will still be an experiment, of course, but I would like it to be an experiment that is directed in a productive manner. So, I shall keep thinking and planning. It’s hard to do more in the middle of the semester. Let me know what you think? Those of you who teach, what are you thinking of doing? Are you looking to change something? Those of you who do not teach, what would you like to see?

Thoughts on Education – 2/21/2012 – A day with publishers

I got a few of my own things done today, including teaching a class, but the majority of today was taken up with activities involving publishers. This was not a bad thing, it’s just different from normal. It was all with a single publishing company, which shall remain nameless. I met with two representatives just before my first class today, and that was very productive. They represent the book that I am currently using and also represent the book that we are probably going to be adopting starting this next school year. It’s not the exact same book, but is instead the brief edition of the one I’m using now. We discussed some of the issues and problems I’ve been having, and it would have been nice to talk to them longer, as we could certainly have talked more at that point. It was nice, as I do like the one-on-one (two-on-one here) interaction, especially with a product that I am currently using.

After my class today, the representatives took the history people out to lunch, and we had a great time just chatting and eating good food. I don’t go to On the Border much, but what I had was very good. It is funny, as they had this symbol used in the menu that represented “healthy choices,” but it was only on three items out of the whole entire menu. I ended up with a fajita salad, which was not marked as “healthy,” but I left off the sour cream and guacamole, which made it not very bad for me at all.

Came back to campus for a bit of office hours and finished up a few things, then it was a drive to Irving. Long drive. A huge accident at the 121/183 split backed up for miles and led to a very long and slow drive. Finally, I made it to the hotel where the history focus group was being held with the publishers. Essentially, they were showing off their product and getting reactions from us as to what we liked, what we didn’t like, and what we would change/improve. I had seen most of it before and was the only one there who had used all of the products shown. Unfortunately, since I do like to talk, and since I had a lot to say about the products that were being used, I probably did talk too much. Still, I hope it was helpful to the others there, and I hope that what I had to say was also helpful to the publishers. It was an interesting evening, but i know that it was more helpful to them and the others than it was to me specifically. It was not a wasted evening by any means, and I did like discussing the material. I also ran into a couple of people from my earlier conference in Key West last fall, but I must say I liked that format better than this one. I know the intention is different, and Key West is nice as well, but I just like delving into the issues over a 2 1/2 day conference better than over a 2 1/2 hour conference. I felt like we just were not able to go into much detail and kept having to move on, whereas I would have loved to just keep going. I guess that’s the education nerd in me, as I could just talk and talk and talk about this stuff all day long. Probably better to keep it short anyway, as I would have just continued to talk otherwise.

And now, I’m back home. Tomorrow, I’m going to have to get to the actual grading I need to do, but it was nice to do something very different for a day.

Thoughts on Education – 2/18/2012 – Who can achieve academic success?

Back to your normally scheduled educational blogging. I’m feeling better finally, and I’m going to take a bit of time to blog here before starting on my main job for today, which is going to be grading.

‘Academically Adrift’: The News Gets Worse and Worse

The beginning has to be the continuing discussion of the assessment of how much students learn in their college education. The latest information that has been released shows a further problem with our higher education system: “While press coverage of Academically Adrift focused mostly on learning among typical students, the data actually show two distinct populations of undergraduates. Some students, disproportionately from privileged backgrounds, matriculate well prepared for college. They are given challenging work to do and respond by learning a substantial amount in four years. Other students graduate from mediocre or bad high schools and enroll in less-selective colleges that don’t challenge them academically. They learn little. Some graduate anyway, if they’re able to manage the bureaucratic necessities of earning a degree.” With teaching at a community college, I do, unfortunately, see mostly those from the second half. And, as I know from experience, when people think of college students, they don’t think of the students I have. Instead, as has been noted, the people who talk about educational policy mostly come from that first group and the people who create educational policy come from that first group. Students like mine are generally ignored in the debate about what to do about academics, which is why I often find the advice and discussion about education to be somewhat irrelevant to who I teach. In fact, even the failures of my students (and there are many) are generally seen as a failure on the part of the student. We blame the students for failing, even when they come into a system not designed for them and where their needs and abilities are not dealt with in a constructive manner. I don’t mean to say that the community college system or my community college is failing, it is just that when I have an expectation that 30-50% of my students will either withdraw, fail, or get a D out of my course, then we have to be working at a different standard. You don’t see that at elite or even normal 4-year colleges, yet most of what you see out there that involves higher education deals with those students. There are some community college specific resources, but they don’t drive the national conversation about education.

As this report shows, that bottom level of college students are more likely to come out of school with few skills and few prospects, where the likelihood is that they “are more likely to be living at home with their parents, burdened by credit-card debt, unmarried, and unemployed.” And, that makes it more difficult to justify an education to the students and to justify the cost of that education to those who pay for it. Of course, as I have noted so many times, articles like this love to point out the problems, but they never say much of anything about solutions. In fact, the implication of the end of the article is that maybe this research isn’t really correct and that we need to do our own research to find out the real truth. But I see the failures every day. We know that a certain number of students will simply never make it through, no matter what we do. It is sad, but it is true. But are we giving value to the rest of the students is the real question. I hope that we are, and I know that our current assessment craze is trying to prove that. I guess I don’t have anything more profound than that to say about it. It is definitely one of those things that makes teaching hard and makes justifying the money and time spent on teaching hard. But the question to ask always is, would we prefer a system where we never give any but the top people a chance at an education?

I came across two other related articles on teaching that I thought I would talk about for the rest of this blog post:

Colleges looking beyond the lecture

I picked this one because it is one of the things that pisses me off over and over in reading articles about changes in teaching. Here’s the reason: “Science, math and engineering departments at many universities are abandoning or retooling the lecture as a style of teaching, worried that it’s driving students away.” Where are the humanities and social sciences in this? Why is it only STEM that is trying to make changes. Yes, I can find a few history sites out there, but overwhelmingly if you’re talking about changing up education or the use of technology, it comes back over and over to STEM as the place where changes come from. So, wonderful, colleges are looking beyond the lecture in these areas because students aren’t succeeding with the lecture. Does that mean the lecture is working elsewhere? Or is it because the lecture is such an expected part of other areas of education that we don’t even question its utility.

So, the article goes on to talk about the challenges of the lecture system — low student learning, the ability of students to get the same information elsewhere, and low retention. What is interesting is the last part of the article that talks about the solutions, which is mostly to stop lecturing. While they don’t use the term “flipping” the classroom in this article, that is what is discussed over and over. So, nothing really new over things I have discussed in the past. What is interesting is that most of the solutions talk about “experimental” classes that are tiny in comparison to the large lecture classes. But, is that an acceptable solution? Obviously, we have large classes because that’s what makes the most monetary sense, and we are not going to switch to a situation where there are no more big classes. So, I found the solutions here to be unrealistic.

At M.I.T., Large Lectures Are Going the Way of the Blackboard

This article is certainly related to the last, and I include it here, as this is the direction that everyone looking at education reform is looking at, based simply on how many articles there are out there. It is, of course, also what I am considering, which is why I pull every article like this out to look at more closely. But then, what do I see? “The physics department has replaced the traditional large introductory lecture with smaller classes that emphasize hands-on, interactive, collaborative learning.” Back to STEM. Back to ending the large classes. Sigh.

Of course, if we had the money and resources, I would certainly jump at trying this: “At M.I.T., two introductory courses are still required — classical mechanics and electromagnetism — but today they meet in high-tech classrooms, where about 80 students sit at 13 round tables equipped with networked computers. Instead of blackboards, the walls are covered with white boards and huge display screens. Circulating with a team of teaching assistants, the professor makes brief presentations of general principles and engages the students as they work out related concepts in small groups. Teachers and students conduct experiments together. The room buzzes. Conferring with tablemates, calling out questions and jumping up to write formulas on the white boards are all encouraged.” But, we don’t have that type of classroom, those types of rooms to work with, teaching assistants, or anything like that. Plus, as the first article made the distinction, is this something that only works with the top level of college students or could it work for the bottom as well? A big question that I do not know the answer to. But since this is where the current push to change the system is going, I am trying to find out all that I can.

That’s why I started with the first article, as I think that we do design and think about the top level of students first, but that often leaves the bottom level out. And, I teach a good portion of students who are at that bottom level. I am trying to change their opportunities, but so often it does seem like the solutions I’m looking at require more money, time, and resources than are available to me. And yet, we’re also facing continuous budget cuts because even at the level we are now, we seen as being too expensive. I don’t know what this means, but it does make the job more difficult. Being innovative, creative, and improving student success on the cheap is very difficult.

Thoughts on Education – 2/12/2012 – Is Technology the Solution?

I haven’t had much time to sit down and think about education since Thursday. It’s funny how the weekends slip away from you. I do have a big backlog of articles after having not done them on either Thursday or Friday, so I’m going to stick with more reviews today. I haven’t quite figured out what’s a good mix here, more of my own stuff or more article reviews. Of course, even in the article reviews, I am including a lot of my own thoughts as well. Right now, I’m doing article reviews when I get 4-5 articles I want to look at. However, I do look at so many places for information through the week, that it is honestly quite hard not to have that many articles to examine.

Using Technology to Learn More Efficiently

OK, so to start, just ignore the large Jessica Simpson lookalike on the page there, as distracting as her stare is there. I was interested in the article from the title, which is what gets me to save most of them for review later. So, often as I’m sitting down here to write about them, I am reading them for the first time as well. Sometimes they are so irrelevant or don’t do what I want that I simply don’t do anything with them at all, such as this one today. This one almost got a delete as well, but the concept is at least interesting, even if it links up to an older style of learning that I don’t want to encourage in my own classroom — flash cards. The article profiles a company that is digitizing flash cards and remaking them to encourage better retention and more honest use of flash cards. The more compelling idea is the creation of a schedule and the push for accountability to the students to complete their work. As the article notes, this is really an attempt to reduce the unproductive cramming before an exam and open up a broader studying schedule. However, the ultimate limitation here is the students. They are the ones who have to make the decision not to cram at the last minute, and I have a feeling that the students who would do this with this program would be the same ones who would be least likely to put off all of their learning to the last minute anyway. Still, I’m all for accountability, especially if it could be integrated with that idea from yesterday on using Google Docs to gauge student progress. So, maybe as a tool that an instructor could put together and release to the student, this could work.

The Gamified Classroom (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4)

“Today, students are expected to pay attention and learn in an environment that is completely foreign to them. In their personal time they are active participants with the information they consume; whether it be video games or working on their Facebook profile, students spend their free time contributing to, and feeling engaged by, a larger system. Yet in the classroom setting, the majority of teachers will still expect students to sit there and listen attentively, occasionally answering a question after quietly raising their hand. Is it any wonder that students don’t feel engaged by their classwork?”

This, again, goes back to the issues I’ve talked about in several other posts, especially the last one. If we are talking about student engagement, then I think we are failing with the lecture model, especially to the most current generation of students, which is who this article series concerns. I just have to look out at my own classes on lecture days to see the problems, with maybe 1/3 paying active attention, 1/3 paying occasional attention, and 1/3 completely disengaged from the material. Of course, is gamification the answer? Of course not. But can we learn something from this educational trend? Very likely. Perhaps it can bring in greater engagement and even foster creativity rather than rote learning.

The role of technology can both help and hinder learning. The article refers to a number of ways that technology can help engagement, through having the students involved in project based learning and higher levels of engagement, using both apps and clickers. What is interesting is what the author sees as one way that technology is reducing that engagement as well, the smartboard. I’ve not seen that criticism before, as the smartboard is often held up as one of the prime ways to engage students. “Unfortunately, our classroom is often filled with technology that only exists to better enable old styles of teaching, the biggest culprit being the smartboard. Though it has a veneer of interactivity, smartboards serve only as a conduit for lecture based learning. They sit in front of an entire classroom and allow a teacher to present un-differentiated material to the entire group. Even their “interactive” capabilities serve only the student called upon to represent the class at the board.” I have been suspicious of smartboards as a save-all, but I had never really been able to figure out why I didn’t like them. I find this argument compelling. From my own point of view, they seem to just be a new version of the chalk board, offering nothing more than you can find with the method.

“In schools, our students should be using technology to collaborate together on projects, present their ideas to their peers, research information quickly, or to hone the countless other skills that they will need in the 21st century workplace–regardless of the hardware they will be using in the future. If we’re just using tech to teach them the same old lessons. . . we’re wasting its potential. Students are already using these skills when they blog, post a video to YouTube, or edit a wiki about their favorite video game. They already have these skills; we have to show them how to use them productively and not just for entertainment. This is where Gamification comes in. Games are an important piece of the puzzle–they are how we get students interested in using these tools in the classroom environment.” I agree. Ha! What I always tell my students not to do, present a big quotation and say they agree, but I guess I’ll hold myself to a lower standard than them. Still, I think this is an insightful look at the problems with just throwing technology at the problem. You can’t just hand teachers technology and expect them to transform everything. Technology is not the solution, although effective teaching with effective technology could be part of the solution.

The last two Parts of the series deal with how this might take place in practice. I’m not going to go through all of that here, as the information is diverse and hard to summarize. So, check it out if you’re interested. I think what is most interesting is the push for self-pacing and self-motivation for students. Tying completion to rewards beyond simple grades and pushing the students to do more. This is an interesting idea, but I do wonder if our students are ready for this. That is always the problem with these articles, that they project these things into an ideal world where students are not motivated because we aren’t motivating them. Yet, the real problem is often much more complex. Our students are as varied as can be, and the reasons for motivation or lack of motivation are varied in the same way. How do you motivate students who are working two jobs, taking care of kids, sick, taking care of sick family members, in school only because their parents think they should, in school only because they think the should, and so forth. In other words, when students aren’t required to be there, such as at college, how does this push differ? Something to think about.

The loss of solitude in schools

And, I’ll close for today with an opposite view. Here, the author is warning against the push for project-centered education, one where we emphasize interaction and group work over individual absorption of material. She makes the case that education is inherently a solitary process, where we engage with and absorb difficult material until we learn it. As she says, the emphasis on group work and interaction produces students that “become dependent on small-group activity and intolerant of extended presentations, quiet work, or whole-class discussions.” In other words, they forget how to learn on their own.

She also notes that the push away from the “sage on the stage” can be just as damaging for students. “Students need their sages; they need teachers who actually teach, and they need something to take in. A teacher who knows the subject and presents it well can give students something to carry in their minds.” I have never done much with small group work, so I can’t say one way or another how this works. I have generally done either lecture or discussions. I don’t know how to evaluate small group work, and so I have not done it. Perhaps this is short-sighted of me, but I just don’t know how to give a grade for group work that is not just on the end project. In other words, how do you hold everyone accountable? I know, from talking with my wife and remembering my own experiences, that group work is inherently unequal and very frustrating for those who want to do a good job, as they generally end up doing most of it. I don’t want to put students in that position, and have never been much for this idea. I could be convinced otherwise, but I am skeptical on the idea of small group work. I know that many of the changes I’m looking at making involve small group work, but I just don’t know what to do with it.

Anyway, enough for today. Please let me know what you think or if you have any responses to the ideas I’m presenting, as I don’t want to be working in a vacuum on this.

Thoughts on Education – 2/11/2012 – A revolution in the classroom?

Here’s a breakdown of the articles on education I’ve come across recently.

We’re ripe for a great disruption in higher education

The core of her argument is here: “But the real disruption comes when you stop measuring academic accomplishment in terms of seat time and hours logged, and start measuring it by competency. As all employers know, the average BA doesn’t certify that the degree-holder actually knows anything. It merely certifies that she had the perseverance to pass the required number of courses.” She is projecting a time when everything is going to be overturned. Where it’s not just the point where online courses take the place of face-to-face courses, but where the whole model of how we teach gets overturned. Who knows if she is right that this is going to happen anytime soon or in our lifetime, as revolutions are predicted all the time, but the argument is certainly compelling. Alternatives to the 4-year, sit-down degree have been growing, and at some point, it is easy to see us reaching a point at some time where we have fewer and fewer “traditional” students. Even now, I know that we could fill as many online classes as we could offer at my community college. My history ones always fill in a day or two after they open, and we could keep going. Of course, then there becomes the question of who is going to take the traditional classes if we just have more and more online classes? Right now, we limit the alternatives, forcing most students to take a traditional, face-to-face class. And, right now, there is a distinct population that wants that. However, at some point we are going to stop being able to keep that gate closed, and students will start going to places that offer more flexibility. The other thing that occurs to me on reading the article is that even our most “non-traditional” offering at my community college, the online course, is still strapped into the traditional course calendar. It starts and ends at the same time, and the guidelines we are given have the students not able to work ahead but instead completing the course like a traditional course. Breaking those boundaries will become necessary I think. We should be moving to classes that are self-paced, classes that work outside of a semester schedule, classes that can be completed in 4-, 8-, 12-, 16-, 20-, 24-weeks or whatever. Classes that start at odd times and classes that end at odd times. I can see the day, at some point, where we have rolling enrollment and completion on a student’s schedule. The student registers and starts, finishing up when he or she finishes, with assignments graded as they come in. We create the content, monitor the course, are available for consultation, feedback, and assessment. In other words, the day where a lot more places look like Western Governors University. And, the scary thing is, I don’t think that’s a bad thing.

Using Google Docs to Check In On Students’ Reading

And, if we are going to move to this more self-paced model, then we need to have better tools to check in on our students as they are doing their work. So, this article’s title certainly seems to go along with that. This is a quite interesting use of Google Docs. He details how to create a spreadsheet to keep track of where students are and what they are doing. As it is shared among all students, everyone can then see whatever common dimension you are looking for. In his case, he was having common reading and having the students post up before each class on how far they had read. That way he knew roughly where all students were, including a class average that gave a decent idea of how far most students were. I could see this used in a lot of different cases for common assignments in a traditional class or with a self-paced class, you have to post up to that in order to keep track of each individual student’s progress as they make their way through a self-paced course. I could see something like this really working well at tracking students on those types of assignments that they do outside of class that don’t have specific end points/assessments (like textbook reading and the like). That gives you another way to check progress rather than just waiting on them to complete a chapter test. The only thing this relies on is the students accurately and honestly recording their progress. I do think this would matter less if you were thinking about a self-paced course than one where it would be embarrassing for a student to show up to class not having read the required reading. With a self-paced course, this tool could also serve to remind the students at regular points that they should be working on some piece of the course.

Harvard Looks Beyond Lectures to Keep Students Engaged

This article was a bit shorter and lighter on substance than I thought when I posted it up to Evernote to read later. Still, it does cover some of these same ideas that something needs to change, as I think many of us can agree. In this case, Harvard is dealing with the problem that “researchers already know what works to promote deeper thinking and learning and it’s not sitting in lectures, taking tests, and then moving on to the next topic. Instead, students need the opportunity to make meaning of what they’ve learned and apply it to real-world challenges.” I can certainly agree with that. What I don’t buy is the last section, which implicitly tells us to wait for Harvard to make its decision on how we should change things, and then we can all rely on their expertise and change afterwards. I’m not waiting for them, and I don’t think the field is either.

Resistance to the inverted classroom can show up anywhere

I’ll close today with this one, which goes back to a concern I raised in the first article. “Many students simply want to be lectured to. When I taught the MATLAB course inverted, all of the students were initially uncomfortable with the course design, some vocally so.” Challenging the way things have always been done is going to lead to resistance. The student in a lecture class is in a passive role. Little is asked of that student, and they can just go through and do the minimum and do fine. Show up, take a few notes, and we will consider you to be learning. I hear that all the time from my colleagues (not going to name any names here), that the students they have won’t even take notes in class. I wonder two things about this.

First, is taking notes the thing we are seeing as the highest level of learning? I hear that more than anything else, that if you aren’t lecturing and the students aren’t taking notes, then learning isn’t happening. I go the route where I give all of my students my lecture notes ahead of time, which they are welcome to bring to class or use a laptop/tablet to access in class. I have had a number of students comment positively about that, saying that it allows them to actually pay attention to what is said in class rather than furiously trying to take notes on it. I’m not sure when it happened, but we seem to have elevated taking notes on a heard lecture to the highest form of academic achievement. Yet, I have plenty of students who don’t take any notes who do well and students who take a lot of notes who struggle.

Second, listening to a lecture and taking notes on it is the most passive of activities for a student. It might seem active to watch the pencils flying out there in class, but, at its heart, this exchange requires very little of the student beyond paying attention. There are not a lot of jobs out there where the ability to listen to 75-minute lectures and take notes about them is going to be a regular part of what they are asked to do. Yet, that seems to me to be the primary skill that we ask of the students. And while it is, why would a student want to change it. All they have to be is a listener and a note-taker.

Of course changing out of the model is going to breed resistance. If you told me that instead of sitting and listening to a lecture, I had to actively participate, presenting my opinions, engaging the material, and thinking and doing, I would have resisted as well. I can’t say it a lot better than this author did: “What I think this illustrates is that there is a cultural expectation about how college classes ought to go that is very hard to change. Many students — and faculty! — in higher education are sold on what I called the renters’ model, which is basically transactional. I pay my money and inhabit this space while you take care of my needs, and when I’m done I’ll move on. The inverted classroom is one style of teaching that insists on ownership. There will be some friction when two fundamental conceptions of class time are in such disagreement with each other, no matter how much sense it might make in your content area.” It is something I worry about on a regular basis about making change to my class. The question is, do we let expectations hold us back or do we move forward anyway and try to change those expectations?