Thoughts on Education – 3/11/2012 – What is broken in higher education?

I’ve taken some time off as we begin Spring Break here to get some of my own stuff done. We are doing a big clean out around the apartment, as we are probably going to move out of out apartment when our lease is up, and it would be nice to move a lot less stuff. I also sat down to start our taxes this weekend. Other than that, I’ve been trying to do “other” things, such as catching up on magazine/free reading, going through paperwork, and such things like that.

On my plate also is catching up on some of the articles I’ve been saving up. I’m trying to group them into themes, and today’s theme is articles that talk about what’s wrong with higher education today. I’m going to hold off on my own opinion here to open this post, as that will come out as we move along here.

The first article I came across is this one from the Chronicle of Higher Education. At its center is a YouTube video that talks about why students think that the lecture is a failing model for education. Three big points that come out of it, I think:

- First, they talk about lectures being boring, especially those where the professor simply reads off of the PowerPoint. This is undeniably true, and not just for students. I have been to enough conferences and presentations where this same thing was done to have experienced it myself many times. Solution? Well, we certainly could use some training for how to teach/lecture. Also, professors just need to care more. If that’s what they are doing, then it’s hard to call that really teaching. I imagine, however, that a lot of this is exaggeration on the part of students as well, as I know there are many students who would be dissatisfied/bored with anything that they were told they had to do, which would include listen to a lecture.

- Second, a comment that resonates with me is the one about attention spans and the 90-minute class. While we don’t have 90-minute classes at my community college, we certainly have mostly 75-minute classes. When the average human attention span is 20-25 minutes at the outside, we are asking even the best and most dedicated students to do something unreasonable if we expect them to sit and pay attention to a lecture for 75 minutes at a time. Yet, I do that very thing every day I’m in class.

- Third, and really the comment that stood out to me the most, one students said that they are told over and over to think outside the box, yet the ones who never seem to innovate are their own professors in their teaching styles. Yup. Can’t say anything more than that is spot on.

A second interesting article also addresses these concerns. In “Why School Should be Funnier,” Mark Phillips discusses the uses of humor in the classroom. I think that we do too often take the view that classes and college are serious, important things. As he says in the article, he’s not talking about throwing in a few jokes but about really seeing the absurdity of the situation we are put in. I address this regularly with my class, as I am very open about the failures of the lecture model and how the fact that they are expected to sit here and pay attention for all this time through the semester is, to a certain extent, absurd. My students (I hope!) appreciate it when I give the sly asides, the knowing winks, the “real reason you need to know this,” and all of the other things that I try to do to keep them engaged and going in a format that encourages torpor and boredom.

A third article focuses on the problems of who is driving educational reform. In this case, the experts are pulling us forward to the future. Educational reformers rely on educational experts to tell them what they should do to fix things. Usually, these experts are located outside of schools, connected with specific political ideas, and intent on fixing one part of the system at a time. In each of these cases, we end up with a failure of reform. I have not been asked much about what I think works or not, that’s for sure. In fact, the one group that usually does ask me what works or not are the textbook publishers. I hear from multiple publishers all the time who want me to tell them what is working and what doesn’t. Yet, as you move up the chain of administration or outside of my college completely, I have yet to have any input on the reforms coming down to me. It does always blow my mind every time I see the next thing coming through, and I have to wonder who thought that up. Perhaps we need a revolution from below to fix things.

To close today (yeah, I know, not a long one today, but I am on vacation . . .) is an article about the path of college from The Huffington Post. In it, the author brings together multiple different studies to talk about something very important when considering what is broken in higher education. At the heart of it, we still have an assumption that college works as a straight line, where you graduate from high school, pick a college, go to it, and graduate in four years. Even at a community college, we look at that same thing as the norm, with just the detour of a community college first. I must admit, that is exactly what I assume still as well, despite the evidence in front of my face every day. The reality is that students start, stop, transfer around, switch degrees, leave for 15 years, have kids, hold multiple jobs, get sick, take care of sick family members, join the military, drop out, etc. To shove everyone into that little box of four-year completers is just stupid, when you get right down to it. And, our funding at the college level is dependent on that completely. We fail a student if we can’t get them out in 2 years for community college and 4 years for college. Yet, how many people really do that? How many want to do that? Our funding levels depend on a myth of college completion. Our assumptions about how to teach and advise students works on this myth. Our assumptions on who a student is and what he or she should do in our classes rests on this myth. What is broken is the way we do things. What needs to be fixed is the way we do things. While it is easy to blame the students for that whole list of things that I said up there, the reality is that the students are going to be that no matter what. We have to figure out how to adapt to it. And the people who give us the money to be able to do this had better get it in their heads that just because we can’t say that 100% of our students graduated from our community college in 2 years, that does not mean that we are failing.

Thoughts on Teaching – 2/26/2012 – A grading weekend

OK. I’m cheating on the date a bit here, since it just turned past midnight here, but I will probably get a Monday blog out, so I went ahead and put this with a Sunday date.

Just a note here as to why I haven’t posted all weekend. It’s a grading weekend! I took Friday off from grading after working through assignments last week, but Saturday and Sunday were full-on grading extravaganzas. For any of you who teach out there, you know how it is. I spent a good 8-10 hours each day working on my grading. My mom, who also teaches at a community college, sympathized this morning, although we have opposite schedules on our big grading times. Her strategy is to get up earlier and earlier in the morning to grade, whereas I just stay up later and later grading. This weekend, I stopped grading after 10pm each day, and this week is going to be similarly busy, as I have a lot of grading left to do. That’s the problem with setting up the class to have three major turn-in points for the students, as it means that when each of those points hit, I have around 2 major assignments from each of my 180 students to grade. I typically try to get things back to my students within a week from when they gave them to me, but that’s not going to happen this time. I am actually on the week after schedule so far, but I can already tell that I’m going to fall behind that schedule very soon, as there simply are not enough hours in the day to get things back that quickly. But I will keep working and keep the students notified of my progress, and that should be ok. I’ve noticed that, as long as you are honest about when the assignments will be graded, the students don’t mind not getting their work back for a while. It’s only when they have no idea what’s going on and when they are going to get anything back that they start to freak out.

In all of it, I must say that the grading went well. I did my usual of holing myself up in the back bedroom for both days, putting on either music or movies and just pounding out the grading. I graded roughly 50 essays each on Saturday and Sunday, graded using a grading rubric in turnitin.com. Also, today, when I finished up the second set of 50 essays, I then had to grade the discussion forum participation for each student and figure up final grades. For this assignment, I had the 2 essays and a discussion forum that figured into the grade for the online class. The first essay (the longer one) counted 40% of the grade, while the second essay and discussion participation were 30% each. So, at the end of my grading time this evening, around 10:45, I posted all of the grades up for those online sections.

And, of course, just as a note for all of those who think that teaching college is some cushy job, no, I don’t get paid anything more for working all weekend. Yes, I could just give all of my students multiple-choice tests and not have to worry about weeks like this (as this grading session will at least last through next weekend, if not longer), but I strongly believe that my students should write and need to write a lot. Yes, I teach 6 sections. Yes, I have 180 students signed up for my classes. But each of them will be assigned to write at least 20 pages for me over the course of the semester, and many will do a lot more than that, as my published word counts are only minimums. Most students will find that completing the assignments in the minimum word count is very difficult, and for many, I will read up to twice that much from them in the semester. Although I might curse myself while I’m in the middle of grading these things, I hope that by getting them writing and thinking and by providing them with feedback to help them improve, I am contributing to their further education and growth. Maybe that’s idealistic of me, but there’s still a little idealism left, even after 10 years of teaching.

Thoughts on Education – 2/22/2012 – Getting a liberal arts education

Back to thinking about education after a couple of days doing other things. I’ve been trying to get something up here every day, but things have been so busy over the last couple of days, that I’ve been taking a quick way out a couple of days. So, I want to get back into thinking about some of the big educational ideas out there. There have been a few articles on getting an education, largely about getting a liberal arts education, that have passed through my Evernote, so I thought I’d bring them together here.

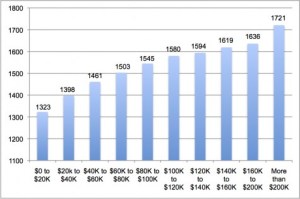

I wanted to open with this chart. It comes from a short article here. I don’t even really need to say anything about it, but I will anyway, as the chart is certainly provocative:

I guess the questions out of this are, what does the SAT really test and what does looking at a standardized test tell us about student progress. The first I learned from a summer of teaching for Princeton Review, which is that the SAT tests you on your ability to take the SAT. That’s about it, since if you know the tricks of taking the SAT, you can do well regardless of your actual knowledge. I can only guess that the fact that SAT scores increase as you go up in income probably reflects the greater availability of SAT prep courses as you go up in income. Or even sadder, maybe it’s that our whole education system is set up to help the richest succeed overall, so what knowledge that is tested on the SAT is more likely to come from the wealthy. On the other side is, of course, the question of how well a standardized test actually measures student ability or progress. Increasingly we come to rely on these high-stakes tests, but do they actually test ability, or do they just test access. In other words, if you are rich and can afford to send your kids to the best private high schools, are you more likely to do well on the SAT tests because of that. I don’t know the answer, but I suspect it’s a combination of all of this.

Then comes two articles on what value there is in the education that students get out of the college they go to. This discussion apparently followed out of a previous article about the ties between Wall Street and the Ivy Leagues. I’m not so interested in that, but I thought the further discussion about the liberal arts degrees and their relevance today were interesting. Of course, my own background as a history major makes me even more interested. I like this paragraph as a starting point from the first article: “Let’s say you’re a history major with a specialization in 18th century Europe from Yale. It may be that, from the economy’s perspective, your time at Yale taught you to think, research and write, which are all skills that can be used in a wide variety of upper-management positions. But that’s not what you think your time at Yale taught you. You think your time at Yale taught you about 18th century Europe. That’s what you spent all your time studying. That’s what you got graded on. And that’s why you’re nervous. There aren’t all that many jobs out there asking for a working knowledge of the Age of Enlightenment.” We talk about these skills that we expect our students at a community college to come out with, but I never really thought about the fact that students might not see or value those skills, as it is not obvious that is what they are really learning. It’s really a question of perception here. As Ezra Klein notes, “. . . it’s a problem that so many kids are leaving college feeling like they don’t have the skills necessary to effectively and confidently enter the economy.” While he is discussing high level education, I think there’s a similar problem at the community college level, as students are even more skills focused at that level. They want to know explicitly what the value of their education is. Simply telling them that learning history will be valuable in the long run doesn’t do much for them. Yet, when you point to these skills — the ability to read, write, think, evaluate, argue, and so forth — they don’t see those listed in the jobs they are seeking, even if those are the skills that employers might really want. I’ve heard this described before as college being short-hand for employers that a graduate has these skills, but that doesn’t help the actual graduate get a job if he or she does not know that they are valuable for that reason rather than for the degree they have. I think this is something we need to emphasize more from the college perspective, but I think that employers also need to be more open about it.

Following in that vein, there was a similar article discussing the results of a concentration on a liberal arts education. Daniel de Vise states – “We tend to offer some – typically our more disadvantaged, low-income populations – a more limited education that may prepare them for jobs for two or three years before they need to be re-trained. Meanwhile, we tend to offer others – disproportionately a more privileged group – a lifelong, liberal education that appreciates over time, preparing them for entire careers, and for jobs that may not even exist yet in our rapidly evolving economy.” We certainly go with the first side at the community college level because that is what we see ourselves as, as much technical trainers as transfer teachers. We do think of ourselves as teaching transfer students in the standards, but the reality is that many of our students are even pursuing a degree for the work advancement that it can bring. And this article comes back to that issue of skills. What he calls “liberal education” is at the center of the transfer of those skills from the Klein article earlier, in that a liberal education delivers an ” education that focuses on the development of capacities such as writing, effective communication, critical thinking, problem-solving, and ethical reasoning. These skills are practical, transferrable, and essential for the life-long learning that we all need if we are to thrive in a world that is complex, diverse, and ever-changing.” He warns against taking away that education in focusing in on technical education in fields that might not last or in training that will have to be renewed soon. Again, I think we need to emphasize these skills more. And, I guess I’m pointing to myself here, as I never really make it all that apparent that these are the valuable skills in the whole process. I know we get caught up in the specifics of our subjects, but delivering a course as simply learning history or english or math or whatever will never be as valuable to a student as learning skills for the real job market out there. As well, if our students graduate or transfer only knowing that they have accumulated the correct courses to graduate, then they will not see the value of what they are learning. Of course, as I noted above, if employers aren’t honest about what they want out of a college graduate, then those skills won’t be seen as valuable either. They need to be explicitly sought in the job market for it to be relevant for me to tell students that they are learning these valuable skills. It has to be a circle starting somewhere, I guess. But should it start from my end or from the employers?

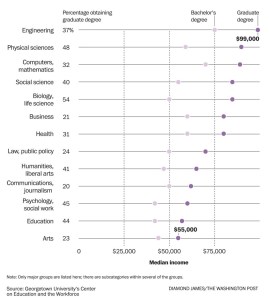

On the theme of a degree telling employers something, this article on the value of a graduate degree is also relevant. As noted, a master’s degree or higher “signals to employers that recipients can complete a demanding program and that they have already been vetted by an institution.” It denotes a set of skills rather than a specific skill. While nothing in this article is particularly groundbreaking, it really just extends the last two I’ve discussed here into the graduate realm. Of course, the value of the graduate degree does vary by field, and I found their graphic to illustrate this well:

This, or course, shows that for me, there was a bump for getting my degree, although certainly from a lower level to start and a lower gain as well. Also, as noted a master’s degree is quickly become a standard rather than an option. This is true for me. So, regardless of the skills that I’m supposed to have learned from my degree, I simply had to have it. I could not have gotten my current job without a master’s degree, regardless of what skills I actually gained. And this, of course, is the other side of all of this I’ve talked about today. If the degree is a symbol of skills learned, then we have to be teaching those skills. I think I am, but are we all? Does every college education show those skills? Just something to think about.

Thoughts on Teaching – 2/19/2012 – First major assignments due

It’s the joy that anybody who is a teacher knows — the joy of the first major assignment coming due. It’s the point where students who have skated by not doing much are going to have to put up or shut up. And for me, that point has been reached. In my hybrid classes, their assignments are scattered and due over about a 2 week period, so it’s not quite as bad with them, but with the online classes, they are turning in their first big one tonight. And, since I’m in online office hours tonight, I am here and witnessing it blow by blow. What that has meant is that I have been hearing and seeing all of the excuses roll by as to why something is not working or why things will not be turned in on time. Actually, I haven’t seen that many of those yet, but it’s almost 8pm now, and the assignment closes at midnight. So, as it gets closer and closer, the fear-induced excuses will grow. On the positive side, I have seen a lot of drafts so far, which is very good. Drafting means higher levels of organization and preparedness and generally leads to better grades overall. Of course, even then, the assignment has been open for 5 weeks, and I am seeing even drafts only in the last couple of days. I know it’s a joke to say an assignment is open for 5 weeks, as very, very few students will do any work on something more than a week before it is due. Most will do it a day or two before, so a good number are working furiously to finish it right now.

I’ve also thrown in a different wrench this time to their plans (lovely mixed metaphor there). They get all of the information for their assignment from the textbook website, but they actually turn it in on turnitin.com. So, they have to take the extra step of making sure they turn it in to the correct place. As of right now, I have already been contacted by two who realized they turned it in at the incorrect place, and I’m sure there will be more who will realize it at a later point. As to excuses, I’ve had two so far — a child in the hospital and a crashed computer — both are probably legitimate (the first definitely so), and those have been dealt with. The more creative excuses come as we get closer to the time when everything is due. I do take late assignments at a 10-point penalty per day, but I don’t actually say that up front, as I don’t want students abusing that option.

For now, it is the time when I start to see who is really serious about the class and who is not. It’s funny that it comes to that, but it is true as well. A good portion of my students do not make it even to the first assignment of the semester. They are already lost before they’ve even gotten any significant grades, and there is not much I can do about it. I can notify them that they have missed the assignment (we have an Early Alert system that sends them an official email and letter from the college), but that’s about all I can do. This semester, there has already seemed to be a larger number in classes overall here at my community college that are not showing up. One of my hybrid sections is already down a third in attendance. I’ll have a better idea of how the online classes sit after this weekend, so I can’t say anything there yet. I’ve talked to some colleagues and even my classes themselves, and everyone has noted a larger than normal number of students who have signed up for classes and not even made it past the third or fourth week. I don’t really know why or what would make this semester any different than the others.

And so I sit and monitor my classes for now. I have some other projects I’m working on, so I am doing those on the side while I’m here monitoring my email and my online office hours room, but most of it is just sitting here and monitoring. Not the most exciting thing, but then teaching, especially online, does devolve into a lot of waiting on the students to do their thing so that you can do your thing. By tomorrow, I’ll have a mountain of grading to do. But for now, I wait, do some other things, and keep checking to try to avert whatever crises I can.

Thoughts on Education – 2/18/2012 – Who can achieve academic success?

Back to your normally scheduled educational blogging. I’m feeling better finally, and I’m going to take a bit of time to blog here before starting on my main job for today, which is going to be grading.

‘Academically Adrift’: The News Gets Worse and Worse

The beginning has to be the continuing discussion of the assessment of how much students learn in their college education. The latest information that has been released shows a further problem with our higher education system: “While press coverage of Academically Adrift focused mostly on learning among typical students, the data actually show two distinct populations of undergraduates. Some students, disproportionately from privileged backgrounds, matriculate well prepared for college. They are given challenging work to do and respond by learning a substantial amount in four years. Other students graduate from mediocre or bad high schools and enroll in less-selective colleges that don’t challenge them academically. They learn little. Some graduate anyway, if they’re able to manage the bureaucratic necessities of earning a degree.” With teaching at a community college, I do, unfortunately, see mostly those from the second half. And, as I know from experience, when people think of college students, they don’t think of the students I have. Instead, as has been noted, the people who talk about educational policy mostly come from that first group and the people who create educational policy come from that first group. Students like mine are generally ignored in the debate about what to do about academics, which is why I often find the advice and discussion about education to be somewhat irrelevant to who I teach. In fact, even the failures of my students (and there are many) are generally seen as a failure on the part of the student. We blame the students for failing, even when they come into a system not designed for them and where their needs and abilities are not dealt with in a constructive manner. I don’t mean to say that the community college system or my community college is failing, it is just that when I have an expectation that 30-50% of my students will either withdraw, fail, or get a D out of my course, then we have to be working at a different standard. You don’t see that at elite or even normal 4-year colleges, yet most of what you see out there that involves higher education deals with those students. There are some community college specific resources, but they don’t drive the national conversation about education.

As this report shows, that bottom level of college students are more likely to come out of school with few skills and few prospects, where the likelihood is that they “are more likely to be living at home with their parents, burdened by credit-card debt, unmarried, and unemployed.” And, that makes it more difficult to justify an education to the students and to justify the cost of that education to those who pay for it. Of course, as I have noted so many times, articles like this love to point out the problems, but they never say much of anything about solutions. In fact, the implication of the end of the article is that maybe this research isn’t really correct and that we need to do our own research to find out the real truth. But I see the failures every day. We know that a certain number of students will simply never make it through, no matter what we do. It is sad, but it is true. But are we giving value to the rest of the students is the real question. I hope that we are, and I know that our current assessment craze is trying to prove that. I guess I don’t have anything more profound than that to say about it. It is definitely one of those things that makes teaching hard and makes justifying the money and time spent on teaching hard. But the question to ask always is, would we prefer a system where we never give any but the top people a chance at an education?

I came across two other related articles on teaching that I thought I would talk about for the rest of this blog post:

Colleges looking beyond the lecture

I picked this one because it is one of the things that pisses me off over and over in reading articles about changes in teaching. Here’s the reason: “Science, math and engineering departments at many universities are abandoning or retooling the lecture as a style of teaching, worried that it’s driving students away.” Where are the humanities and social sciences in this? Why is it only STEM that is trying to make changes. Yes, I can find a few history sites out there, but overwhelmingly if you’re talking about changing up education or the use of technology, it comes back over and over to STEM as the place where changes come from. So, wonderful, colleges are looking beyond the lecture in these areas because students aren’t succeeding with the lecture. Does that mean the lecture is working elsewhere? Or is it because the lecture is such an expected part of other areas of education that we don’t even question its utility.

So, the article goes on to talk about the challenges of the lecture system — low student learning, the ability of students to get the same information elsewhere, and low retention. What is interesting is the last part of the article that talks about the solutions, which is mostly to stop lecturing. While they don’t use the term “flipping” the classroom in this article, that is what is discussed over and over. So, nothing really new over things I have discussed in the past. What is interesting is that most of the solutions talk about “experimental” classes that are tiny in comparison to the large lecture classes. But, is that an acceptable solution? Obviously, we have large classes because that’s what makes the most monetary sense, and we are not going to switch to a situation where there are no more big classes. So, I found the solutions here to be unrealistic.

At M.I.T., Large Lectures Are Going the Way of the Blackboard

This article is certainly related to the last, and I include it here, as this is the direction that everyone looking at education reform is looking at, based simply on how many articles there are out there. It is, of course, also what I am considering, which is why I pull every article like this out to look at more closely. But then, what do I see? “The physics department has replaced the traditional large introductory lecture with smaller classes that emphasize hands-on, interactive, collaborative learning.” Back to STEM. Back to ending the large classes. Sigh.

Of course, if we had the money and resources, I would certainly jump at trying this: “At M.I.T., two introductory courses are still required — classical mechanics and electromagnetism — but today they meet in high-tech classrooms, where about 80 students sit at 13 round tables equipped with networked computers. Instead of blackboards, the walls are covered with white boards and huge display screens. Circulating with a team of teaching assistants, the professor makes brief presentations of general principles and engages the students as they work out related concepts in small groups. Teachers and students conduct experiments together. The room buzzes. Conferring with tablemates, calling out questions and jumping up to write formulas on the white boards are all encouraged.” But, we don’t have that type of classroom, those types of rooms to work with, teaching assistants, or anything like that. Plus, as the first article made the distinction, is this something that only works with the top level of college students or could it work for the bottom as well? A big question that I do not know the answer to. But since this is where the current push to change the system is going, I am trying to find out all that I can.

That’s why I started with the first article, as I think that we do design and think about the top level of students first, but that often leaves the bottom level out. And, I teach a good portion of students who are at that bottom level. I am trying to change their opportunities, but so often it does seem like the solutions I’m looking at require more money, time, and resources than are available to me. And yet, we’re also facing continuous budget cuts because even at the level we are now, we seen as being too expensive. I don’t know what this means, but it does make the job more difficult. Being innovative, creative, and improving student success on the cheap is very difficult.

Thoughts on a Good Class – 2/14/2012 – A gratifying discussion

This week was my first experiment in something different in my classes. I have had discussion days before, so that was not the real difference here. What was different is that I had a day designed purely to explore a single topic in great detail with the students doing all of the preparation work outside of class and coming in simply to discuss that issue. In this case, I set up the material for the discussion by covering the three main tendrils of history that led into the topic — immigration, unionization, and Progressivism. Each of those had been covered in lecture in the days before this class, and so each student should have had a general idea of the historical context in which the incident took place.

In designing my “In-Class Activity” day, I had gone on the web to look at what resources were out there, as I wanted to give the students something that they would not access in a normal class. I did not want a traditional discussion where you have the students go out and read some primary sources and then come back and talk about them. I wanted something different, something that would engage the students in a different way, and yet accomplish the very goals that I always try to reach, having them connect the historical events to the modern age. As well, I wanted them to be confronted with an event that happened to people like them but 100 years earlier so that they could relate to them. Traditional “great man” history does not speak to them in many ways, but getting down to average Americans working hard just to get by speaks well to students, especially the non-traditional ones you find in a community college setting who have been out and worked in the real world.

What I had the students do was go out to the PBS website and watch the American Experience program on The Triangle Fire of 1911. They also were to access a couple of the other resources there, including an introductory essay, biographies of some of the participants, and a few informative pictures in a slideshow. The combination of that material was what they had to do before class, and it was open and available from the first day of class. To get into class on the day of the discussion, the students were required to bring a 1-2 page response to the material. I did not guide them in what they were to write specifically, but left it open to them as far as what they wrote.

It was an experiment in something new, and I really had no idea how it would go. Would they do the work ahead of time? Well, about 80-85% of the students who showed up brought a 1-2 page response. I did not let the rest stay in the class and told them to leave with a 0 for the day. Of those who had a response, I would estimate that about 10-15% of them really didn’t do much of the assigned work. On the other end, about 10-15% went well beyond the required viewings and did their own research. And, another 10-15% couldn’t get all of the resources to work for one reason or another. Of those, a gratifying few did go out and research on their own to find the information. One even told me that the same video was on Netflix streaming, which tells me I should check next time to offer that as a place for students to check.

The next question is, would they engage the material and have something to say about it? I say it was an unmitigated success in this regard. I began the discussion with the most general question possible, “What did you think about the video?” In both of the discussions I’ve had so far, people stopped having a response to that question after about 30 minutes. So, we had 30 minutes of discussion, with me saying quite little except for guiding who would speak next, on just a response to the video. I took notes during that time and did the rest of the discussion off of the topics that they brought up the most. We easily filled the rest of the class period (75 minutes total) with no problems and very few gaps where nobody had anything to say. Of course, some of that is because they were being graded on the discussion, but they really were responding well to the material and had a lot to say at all parts of the discussion. In both classes, I have the feeling that we could have filled much more time if we had it, but that we really did dissect the issues at the time well, while also relating the experiences from that time to the modern day well. I also get the feeling from the responses that I heard that they will remember this event and the discussion we had about it much longer than they probably will the individual things that I lecture on each day.

What do I take away from this? I consider it an overwhelming success on a thing that I wasn’t sure would work. The response was excellent, and students did the work ahead of time, which was something I was very worried about. But why did it work so well? I think some of it has to do with the form of media. There’s something about watching a documentary, especially when you can watch it on your own time rather than being forced to sit there in class and watch it that can be quite engaging. This was a very well done one, which does help as well. Also, it is not “traditional” history. One of the first responses I got, before I even really started the discussion was that almost all of the students had no knowledge of the incident before. They had never heard of it, but they were interested in it. The subject reflects on topics that are relevant in the lives of people who would be at a community college, in that it is primarily about working-age people, mostly women, who are struggling in a system that seems set up against them. The students brought up personal experiences a number of times as they attempted to relate what they had seen there to their own lives, and I did not have to guide them to do this. In fact, I like that word guide, as I felt much more like I was just a guide in the discussion then that I was a leader of the discussion.

I have one more section that will do the discussion tomorrow, and I hope it goes just as well. It’s days and assignments like this that energize me as a teacher and keep me going as an educator.

Thoughts on Education – 2/5/2012

Just try to find any actual news on educational topics on Super Bowl Sunday. I dare you. There’s not much out there, so I really don’t have any articles to bring forward here. Today, I will just put in a brief word on what I’m thinking about these days.

I am unsatisfied with the status quo in education. I seek change. The problem that I have is getting to that change. I have so many ideas but I do not know what will work and what won’t. I have taught in many different ways over the time that I’ve been teaching, and the one constant has been change. I do something different every semester just about, trying things out and seeing what works. If it works, I keep it. If it works sort of, I make changes. If it doesn’t work, I drop it.

I started my teaching career in the most traditional way, working with discussion sections as a graduate student. I did that for five years, working under numerous different professors. My first was a several-hundred-person section under Jackson Spielvogel doing a Nazism and Fascism class. That one was great, as we also had undergrad TAs in the mix, so we were all being taught how to be an effective TA. After finishing up my comprehensive exams, I was put out there as a graduate lecturer. What is interesting about that is that the only guidance I was given for how to teach my own sections was what I had done as a TA. I don’t think the first teaching experiences went badly, but it was certainly a case of learning on the job. And, as my only real model was teaching through lecture, that’s what I did. Lecture and overhead projector images to start, with a move to PowerPoint not too long after that. I taught multiple different classes at grad school, eventually leaving to get a job teaching at the community college where I am now.

Since being here, I have tried to adapt and change. I became an online teacher as that was a requirement of the job. I have moved to other things because I want to reach the students. You know, “engagement” and all of that. I just am not satisfied with passive delivery of information to the students, but finding other options are hard to work with and find. I always feel like I’m on my own with this process. So, I try something, test it out, see how it works, and move on in one way or another. I have slowly moved to a greater online presence, regardless of the delivery format. I now have an extensive online class and supplemental classroom for my in-class students. In fact, I am mostly hybrid now, with all of the quizzing, homework and exams taking place outside of the classroom. The only thing that’s left in class right now are the lectures, and, if you’ve been reading my other blogs here, you know how interested I am in the idea of “flipping” the classroom. I would like to stop being the so-called “sage on the stage” and turn into the class into a more interactive experience for the students, where they learn real skills rather than memorize the material.

The problems with this are many. For one, I still feel like I’m going to be doing this largely on my own. Second, how do you hold the students responsible for doing the work outside of class that has them ready to discuss or work on more specific topics in class? Third, when you are moving away from the traditional ways of assessment, how do you hold to the state standards at that point? These are all things I’m going to be thinking about as time goes by here. I can’t promise I’ll come to solutions, but that’s what’s on my mind.

Now, as I am distracted by the Super Bowl streaming in the window next to me here, I will close for today.

Thoughts on Education, 2/1/2012 – Digital Learning Day

So, Happy Digital Learning Day everyone. OK, so I had no idea it was that day either, but that’s what I found out as I started moving through the educational news that I read every morning. I guess it’s appropriate that I’m working on this project at this time then. I certainly envision any changes that I make to my class to include a significant digital element. In fact, I would like to go ahead and include more of it in my class now, although I am not sure how at this point. Thus, part of what I am doing is trying to figure out how to use all of these new tools out there and how to use the various ideas that I am trying to accumulate. I want to make something new and relevant, and I think that digital technology has to be at the center of it.

What is unfortunate about all of it is how hard it is to find good digital tools for higher education. If I was teaching K-12, there appear to be a lot of apps out there for use, although I, admittedly, have not evaluated them to see if there is real quality or just quantity. For higher ed, there’s a lot of stuff out there for organization, note-taking, and whiteboarding (did I just make up that word?). There’s not much that seems of actual use in a classroom outside of access to resources. in that category, there’s a ton of stuff out there. Simply get the Smithsonian, PBS, TED, or many other apps out there, and you have a ton of free content at your fingertips. If you’re not using Flipbook on an iPad, you are missing out on one of the most spectacular apps that I have ever come across. So, if I want content, I can get it, but that still puts the creation of assignments and linkages on me. I know that’s part of my job, but I kind of expected there to be some actual premade content out there for higher ed, and there just isn’t very much. There are things to show, but not much set up to do. I was talking with my Dean about this, and he suggested that it is because there’s more money in K-12 ed than in higher ed, and that when there is money in higher ed, it goes to research, not to teaching. Certainly, in teaching at a community college, I’m really at the low end of the totem pole for these types of things, but I just imagine what could be out there.

I guess if I was ever to consider a different career, I would love to go into the educational technology field. I’ve considered getting a second Masters in Instructional Design or something like that, but this lack of content seems to be a huge hole in the educational ecosystem. I don’t know if there’s any money to be made in it, but I’m just waiting around for someone to make it at this point.

In thinking about Digital Learning (caps intentional on this day), I have done some reading, and I’ll include a few of the interesting things I’ve looked at here:

http://mindshift.kqed.org/2012/02/on-digital-learning-day-7-golden-rules-of-using-technology/

MindShift is one of those programs I found through FlipBook. I like their discussion of education and technology and read it daily. Again, if you’re interested in the topic, check them out. Anyway, I like this article, as it evaluates the role that technology can play in the classroom. I’m going to have to think on it more deeply at another time. I like the first three points as some basic starting ideas on technology

- Don’t trap technology in a room. This is very true, as the computer lab is something that many of us (like me) have no access to, and so if I want to use technology, trapping it in a single room makes it useless unless you are one of the lucky ones to be able to schedule in that room.

- Technology is worthless without professional development. Completely agree. We don’t get any of this provided to us, and I remain so busy between my teaching life and home life that I don’t get a lot of opportunities to go out and participate in professional development either. I’d love it to be a more real part of my actual job, and I really am going to have to figure out how to make time for it, as it is never going to be just given to me.

- Mobile technology stretches a long way. Use the resources that you have. A good number of people are carrying around high-powered computers in their pocket. Give the students some reason to use them beyond texting.

Beyond that, I need to follow up on some of the links in the article, and I have it saved in Evernote (another great free app) to do just that later.

http://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/happy-digital-learning-day

Another thing I read every day is Inside Higher Ed. They have a number of educational technology resources, and this one celebrates Digital Learning Day as well. Interesting links off of the page mostly, although I like seeing the discussion generally in this blog.

Through the Inside Higher Ed site, I also found this resource. I will check out the video later (my internet connection at home is not cooperating for streaming video from my living room right now, and I don’t feel like moving to the bedroom for a stronger signal). But the broader site of Teachers Teaching Teachers sounds promising and worth checking out more.

Anyway, that’s a few links for today. I have some on gaming in the classroom that I’ll save for sometime in the next couple of days, so hang on for that.