Thoughts on Teaching – 2/26/2012 – A grading weekend

OK. I’m cheating on the date a bit here, since it just turned past midnight here, but I will probably get a Monday blog out, so I went ahead and put this with a Sunday date.

Just a note here as to why I haven’t posted all weekend. It’s a grading weekend! I took Friday off from grading after working through assignments last week, but Saturday and Sunday were full-on grading extravaganzas. For any of you who teach out there, you know how it is. I spent a good 8-10 hours each day working on my grading. My mom, who also teaches at a community college, sympathized this morning, although we have opposite schedules on our big grading times. Her strategy is to get up earlier and earlier in the morning to grade, whereas I just stay up later and later grading. This weekend, I stopped grading after 10pm each day, and this week is going to be similarly busy, as I have a lot of grading left to do. That’s the problem with setting up the class to have three major turn-in points for the students, as it means that when each of those points hit, I have around 2 major assignments from each of my 180 students to grade. I typically try to get things back to my students within a week from when they gave them to me, but that’s not going to happen this time. I am actually on the week after schedule so far, but I can already tell that I’m going to fall behind that schedule very soon, as there simply are not enough hours in the day to get things back that quickly. But I will keep working and keep the students notified of my progress, and that should be ok. I’ve noticed that, as long as you are honest about when the assignments will be graded, the students don’t mind not getting their work back for a while. It’s only when they have no idea what’s going on and when they are going to get anything back that they start to freak out.

In all of it, I must say that the grading went well. I did my usual of holing myself up in the back bedroom for both days, putting on either music or movies and just pounding out the grading. I graded roughly 50 essays each on Saturday and Sunday, graded using a grading rubric in turnitin.com. Also, today, when I finished up the second set of 50 essays, I then had to grade the discussion forum participation for each student and figure up final grades. For this assignment, I had the 2 essays and a discussion forum that figured into the grade for the online class. The first essay (the longer one) counted 40% of the grade, while the second essay and discussion participation were 30% each. So, at the end of my grading time this evening, around 10:45, I posted all of the grades up for those online sections.

And, of course, just as a note for all of those who think that teaching college is some cushy job, no, I don’t get paid anything more for working all weekend. Yes, I could just give all of my students multiple-choice tests and not have to worry about weeks like this (as this grading session will at least last through next weekend, if not longer), but I strongly believe that my students should write and need to write a lot. Yes, I teach 6 sections. Yes, I have 180 students signed up for my classes. But each of them will be assigned to write at least 20 pages for me over the course of the semester, and many will do a lot more than that, as my published word counts are only minimums. Most students will find that completing the assignments in the minimum word count is very difficult, and for many, I will read up to twice that much from them in the semester. Although I might curse myself while I’m in the middle of grading these things, I hope that by getting them writing and thinking and by providing them with feedback to help them improve, I am contributing to their further education and growth. Maybe that’s idealistic of me, but there’s still a little idealism left, even after 10 years of teaching.

Thought on Teaching – 2/24/2012 – Grading the first assignment

OK, so the first major assignment is coming in, and so I am just starting to grade them. It’s always an interesting point when you get to see the first major set of assignments from a group of students. All they’ve had to this point are some chapter quizzes to keep them moderately honest in what work they are doing for the class, but here at the third of the way through point, the real stuff is coming due. I have multiple writing assignments over the course of the semester (6 for the online class and 8 for the hybrid class), and these are the first written ones. So, not only am I seeing their work for the first time, a lot of them are doing real work for me for the first time here. For each of us, this is the point where the class really starts. This is especially true for the class that I just finished grading. I teach the two halves of the American history survey, and so in the spring, I mostly teach the second half. However, I do have one online class that is the first half. Whereas many of the students in my second half class are ones that I’ve had before, all of those in my first half are new to me. So, it really is a new experience all the way around.

What they had to do was work through a Critical Mission within the Connect History system associated with our textbook. There were two written assignments out of that. The Critical Mission had them take on the role of an advisor to Moctezuma as Cortez and his men are approaching. The students have to advise Moctezuma on whether to take a militant approach to Cortez or whether to greet him peacefully. The students are given evidence to work with for it, and they have to put together an argument using the evidence. Anyway, the details aren’t all that relevant, but it does give you the idea of what the students are doing for me. So, I graded their two submissions and discussion forum over last night and this morning, getting all of those out to them early this morning.

It is interesting to see how it goes. First of all, there were 30 people in the class when we started. We are down to 26 now with drops by this point. Of those, 4 have not logged into the classroom in over 14 days, so they are also not really counted. Including those, 11 did not turn anything in for this project, despite multiple reminders throughout the weeks leading up to the project. So, of 30 that I started with, I actually graded 15 projects. The overall results were pretty good for a first assignment. I mean only one or two really hit the mark completely with regards to my expectations, but the results were good overall. What I was actually most impressed with was the discussion participation. I give them a couple of topic options to write on, and generally they give 2-3 sentences at most on the first time out in an online discussion. Instead, here I got long thoughtful discussions with replies that showed they actually had read the other person’s writing and had thought about it. It was impressive for a class of people that have not had me or known my expectations before this point.

I guess I really don’t know what else to say about it. Nothing all that profound here at all, just wanted to share what was a pretty decent feeling for me about an assignment. Yes, so many people didn’t do much of anything on it, but those who did participate actually turned out a good product. That is always gratifying, as it makes me feel like I put together a good class with good instructions if they were able to succeed like that.

P.S. I apologize if this is a bit rambling in nature. I’ve been doing a few other things and keep coming back and adding a sentence or two at a time. So, if it’s disconnected and disjointed, that’s the reason. I’m not going to go back and read over because I’m tired and ready for bed, so everyone will have to take this one as it is. Talk to you tomorrow.

Thoughts on Teaching – 2/23/2012 – An excellent discussion

Just a quick post today, as I need to get some grading done.

I had a spectacular discussion yesterday in one of my sections. We were working through the issues of a Critical Mission from the McGraw-Hill Connect History program. I started off the discussion by asking, “What did you think?” Then, an hour and fifteen minutes later, I ended the class. In other words, they talked for 75 minutes in a productive discussion with no further prompting from me except to interject some comments and call on people to make sure people got to talk. Rare but quite satisfying.

Thoughts on Education – 2/22/2012 – Getting a liberal arts education

Back to thinking about education after a couple of days doing other things. I’ve been trying to get something up here every day, but things have been so busy over the last couple of days, that I’ve been taking a quick way out a couple of days. So, I want to get back into thinking about some of the big educational ideas out there. There have been a few articles on getting an education, largely about getting a liberal arts education, that have passed through my Evernote, so I thought I’d bring them together here.

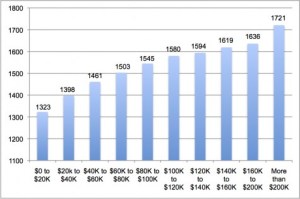

I wanted to open with this chart. It comes from a short article here. I don’t even really need to say anything about it, but I will anyway, as the chart is certainly provocative:

I guess the questions out of this are, what does the SAT really test and what does looking at a standardized test tell us about student progress. The first I learned from a summer of teaching for Princeton Review, which is that the SAT tests you on your ability to take the SAT. That’s about it, since if you know the tricks of taking the SAT, you can do well regardless of your actual knowledge. I can only guess that the fact that SAT scores increase as you go up in income probably reflects the greater availability of SAT prep courses as you go up in income. Or even sadder, maybe it’s that our whole education system is set up to help the richest succeed overall, so what knowledge that is tested on the SAT is more likely to come from the wealthy. On the other side is, of course, the question of how well a standardized test actually measures student ability or progress. Increasingly we come to rely on these high-stakes tests, but do they actually test ability, or do they just test access. In other words, if you are rich and can afford to send your kids to the best private high schools, are you more likely to do well on the SAT tests because of that. I don’t know the answer, but I suspect it’s a combination of all of this.

Then comes two articles on what value there is in the education that students get out of the college they go to. This discussion apparently followed out of a previous article about the ties between Wall Street and the Ivy Leagues. I’m not so interested in that, but I thought the further discussion about the liberal arts degrees and their relevance today were interesting. Of course, my own background as a history major makes me even more interested. I like this paragraph as a starting point from the first article: “Let’s say you’re a history major with a specialization in 18th century Europe from Yale. It may be that, from the economy’s perspective, your time at Yale taught you to think, research and write, which are all skills that can be used in a wide variety of upper-management positions. But that’s not what you think your time at Yale taught you. You think your time at Yale taught you about 18th century Europe. That’s what you spent all your time studying. That’s what you got graded on. And that’s why you’re nervous. There aren’t all that many jobs out there asking for a working knowledge of the Age of Enlightenment.” We talk about these skills that we expect our students at a community college to come out with, but I never really thought about the fact that students might not see or value those skills, as it is not obvious that is what they are really learning. It’s really a question of perception here. As Ezra Klein notes, “. . . it’s a problem that so many kids are leaving college feeling like they don’t have the skills necessary to effectively and confidently enter the economy.” While he is discussing high level education, I think there’s a similar problem at the community college level, as students are even more skills focused at that level. They want to know explicitly what the value of their education is. Simply telling them that learning history will be valuable in the long run doesn’t do much for them. Yet, when you point to these skills — the ability to read, write, think, evaluate, argue, and so forth — they don’t see those listed in the jobs they are seeking, even if those are the skills that employers might really want. I’ve heard this described before as college being short-hand for employers that a graduate has these skills, but that doesn’t help the actual graduate get a job if he or she does not know that they are valuable for that reason rather than for the degree they have. I think this is something we need to emphasize more from the college perspective, but I think that employers also need to be more open about it.

Following in that vein, there was a similar article discussing the results of a concentration on a liberal arts education. Daniel de Vise states – “We tend to offer some – typically our more disadvantaged, low-income populations – a more limited education that may prepare them for jobs for two or three years before they need to be re-trained. Meanwhile, we tend to offer others – disproportionately a more privileged group – a lifelong, liberal education that appreciates over time, preparing them for entire careers, and for jobs that may not even exist yet in our rapidly evolving economy.” We certainly go with the first side at the community college level because that is what we see ourselves as, as much technical trainers as transfer teachers. We do think of ourselves as teaching transfer students in the standards, but the reality is that many of our students are even pursuing a degree for the work advancement that it can bring. And this article comes back to that issue of skills. What he calls “liberal education” is at the center of the transfer of those skills from the Klein article earlier, in that a liberal education delivers an ” education that focuses on the development of capacities such as writing, effective communication, critical thinking, problem-solving, and ethical reasoning. These skills are practical, transferrable, and essential for the life-long learning that we all need if we are to thrive in a world that is complex, diverse, and ever-changing.” He warns against taking away that education in focusing in on technical education in fields that might not last or in training that will have to be renewed soon. Again, I think we need to emphasize these skills more. And, I guess I’m pointing to myself here, as I never really make it all that apparent that these are the valuable skills in the whole process. I know we get caught up in the specifics of our subjects, but delivering a course as simply learning history or english or math or whatever will never be as valuable to a student as learning skills for the real job market out there. As well, if our students graduate or transfer only knowing that they have accumulated the correct courses to graduate, then they will not see the value of what they are learning. Of course, as I noted above, if employers aren’t honest about what they want out of a college graduate, then those skills won’t be seen as valuable either. They need to be explicitly sought in the job market for it to be relevant for me to tell students that they are learning these valuable skills. It has to be a circle starting somewhere, I guess. But should it start from my end or from the employers?

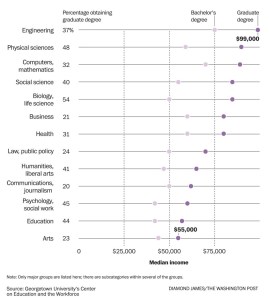

On the theme of a degree telling employers something, this article on the value of a graduate degree is also relevant. As noted, a master’s degree or higher “signals to employers that recipients can complete a demanding program and that they have already been vetted by an institution.” It denotes a set of skills rather than a specific skill. While nothing in this article is particularly groundbreaking, it really just extends the last two I’ve discussed here into the graduate realm. Of course, the value of the graduate degree does vary by field, and I found their graphic to illustrate this well:

This, or course, shows that for me, there was a bump for getting my degree, although certainly from a lower level to start and a lower gain as well. Also, as noted a master’s degree is quickly become a standard rather than an option. This is true for me. So, regardless of the skills that I’m supposed to have learned from my degree, I simply had to have it. I could not have gotten my current job without a master’s degree, regardless of what skills I actually gained. And this, of course, is the other side of all of this I’ve talked about today. If the degree is a symbol of skills learned, then we have to be teaching those skills. I think I am, but are we all? Does every college education show those skills? Just something to think about.

Thoughts on Teaching – 2/20/2012 – A slow day

Today was an uninspiring teaching day. I have reworked lectures at various times over the years, and much of that has been to shorten earlier in the semester lectures so that I can make it further into the time period that I’m covering. Today was one of those lectures where I made cuts that disconnected the material from its real point. So, I struggled through the first delivery to connect everything together and show the students why this was not just a collection of random material but instead was connected and relevant. It worked better by the second class, but both classes were also depressing for another reason. The big problem is that I felt the students were more disconnected than usual today. The drops are starting, so some students are getting out of the class now, but I really have a large number of people simply not showing up. And, of those who do show up, it’s hard to peg very many of them as actually paying all that much attention. Again, it certainly wasn’t my best material at all, but it just reinforces for me the problem with a lecture. When my lecture is going really well, I might have 50-60% student engagement. Today, it felt like 20-30%, which is just depressing overall. In my second class, which is a two-way video class, the high school I was connecting to was not in session, and a lot of people were missing in front of me, so I ended up lecturing to nine people. Twenty-six out of forty in the first class was already low for this time of year, but nine is really depressing. And then to see them mostly disconnected is even worse, as there’s no hiding the fact that you’re not connecting on the material with that few students in the room.

I have been saying for a while that my lectures need to be revised soon, and this lecture was one that needs to be worked with desperately. It might work better as one that is not delivered but that is, instead, seen by the students not as an individual lecture but as a narrative supplement that I have available to enhance the hybrid class going on in the classroom. I guess that’s going to be the question when I do redo the class, whether it’s a full flip or not, which is do I present the lectures at that point in episodic form, like they are now, where there are distinct lectures, or do I format my own material like a book, putting it together in a narrative that the students can engage with like they would the textbook. They can read it in pieces or all at once. I’m thinking of an integrated lecture, with my PowerPoint images combined with the text from the lectures that can be read more like a book. I don’t know, just brainstorming here. I started that a while ago and made it through the first two lectures, coding them in Dreamweaver to bring together a web lecture. Nothing fancy except for integration of the images with text. Still, it would give the students something to read more interesting than just a Word document with an accompanying Power Point. And, this would give a good opportunity to rework the lectures, especially if I am to move beyond the delivery of the lectures and think about them more as a way to deliver my ideas to the student. I can imagine that the lectures would be different if they were aimed at being read rather than delivered. I don’t know. This will be something to think about as I move forward.

I guess all of us who teach have these days, but it was definitely less than inspiring. Beyond that, it was mostly small stuff at work, writing a recommendation letter and weighing in on the choosing of a new textbook for the class. I wish I could say there was more, but that’s about it. I have grading to do, but I did not get any done today, because that filled up my day, and by the time I got home, it was time to pick up the kids. Then, it was chores, homework time with the kids, and dinner. Now, all of the sudden, it’s 10pm. So, I shall sign off for the evening and hope for a more inspiring day tomorrow.

Thoughts on Teaching – 2/19/2012 – First major assignments due

It’s the joy that anybody who is a teacher knows — the joy of the first major assignment coming due. It’s the point where students who have skated by not doing much are going to have to put up or shut up. And for me, that point has been reached. In my hybrid classes, their assignments are scattered and due over about a 2 week period, so it’s not quite as bad with them, but with the online classes, they are turning in their first big one tonight. And, since I’m in online office hours tonight, I am here and witnessing it blow by blow. What that has meant is that I have been hearing and seeing all of the excuses roll by as to why something is not working or why things will not be turned in on time. Actually, I haven’t seen that many of those yet, but it’s almost 8pm now, and the assignment closes at midnight. So, as it gets closer and closer, the fear-induced excuses will grow. On the positive side, I have seen a lot of drafts so far, which is very good. Drafting means higher levels of organization and preparedness and generally leads to better grades overall. Of course, even then, the assignment has been open for 5 weeks, and I am seeing even drafts only in the last couple of days. I know it’s a joke to say an assignment is open for 5 weeks, as very, very few students will do any work on something more than a week before it is due. Most will do it a day or two before, so a good number are working furiously to finish it right now.

I’ve also thrown in a different wrench this time to their plans (lovely mixed metaphor there). They get all of the information for their assignment from the textbook website, but they actually turn it in on turnitin.com. So, they have to take the extra step of making sure they turn it in to the correct place. As of right now, I have already been contacted by two who realized they turned it in at the incorrect place, and I’m sure there will be more who will realize it at a later point. As to excuses, I’ve had two so far — a child in the hospital and a crashed computer — both are probably legitimate (the first definitely so), and those have been dealt with. The more creative excuses come as we get closer to the time when everything is due. I do take late assignments at a 10-point penalty per day, but I don’t actually say that up front, as I don’t want students abusing that option.

For now, it is the time when I start to see who is really serious about the class and who is not. It’s funny that it comes to that, but it is true as well. A good portion of my students do not make it even to the first assignment of the semester. They are already lost before they’ve even gotten any significant grades, and there is not much I can do about it. I can notify them that they have missed the assignment (we have an Early Alert system that sends them an official email and letter from the college), but that’s about all I can do. This semester, there has already seemed to be a larger number in classes overall here at my community college that are not showing up. One of my hybrid sections is already down a third in attendance. I’ll have a better idea of how the online classes sit after this weekend, so I can’t say anything there yet. I’ve talked to some colleagues and even my classes themselves, and everyone has noted a larger than normal number of students who have signed up for classes and not even made it past the third or fourth week. I don’t really know why or what would make this semester any different than the others.

And so I sit and monitor my classes for now. I have some other projects I’m working on, so I am doing those on the side while I’m here monitoring my email and my online office hours room, but most of it is just sitting here and monitoring. Not the most exciting thing, but then teaching, especially online, does devolve into a lot of waiting on the students to do their thing so that you can do your thing. By tomorrow, I’ll have a mountain of grading to do. But for now, I wait, do some other things, and keep checking to try to avert whatever crises I can.

Thoughts on Education – 2/18/2012 – Who can achieve academic success?

Back to your normally scheduled educational blogging. I’m feeling better finally, and I’m going to take a bit of time to blog here before starting on my main job for today, which is going to be grading.

‘Academically Adrift’: The News Gets Worse and Worse

The beginning has to be the continuing discussion of the assessment of how much students learn in their college education. The latest information that has been released shows a further problem with our higher education system: “While press coverage of Academically Adrift focused mostly on learning among typical students, the data actually show two distinct populations of undergraduates. Some students, disproportionately from privileged backgrounds, matriculate well prepared for college. They are given challenging work to do and respond by learning a substantial amount in four years. Other students graduate from mediocre or bad high schools and enroll in less-selective colleges that don’t challenge them academically. They learn little. Some graduate anyway, if they’re able to manage the bureaucratic necessities of earning a degree.” With teaching at a community college, I do, unfortunately, see mostly those from the second half. And, as I know from experience, when people think of college students, they don’t think of the students I have. Instead, as has been noted, the people who talk about educational policy mostly come from that first group and the people who create educational policy come from that first group. Students like mine are generally ignored in the debate about what to do about academics, which is why I often find the advice and discussion about education to be somewhat irrelevant to who I teach. In fact, even the failures of my students (and there are many) are generally seen as a failure on the part of the student. We blame the students for failing, even when they come into a system not designed for them and where their needs and abilities are not dealt with in a constructive manner. I don’t mean to say that the community college system or my community college is failing, it is just that when I have an expectation that 30-50% of my students will either withdraw, fail, or get a D out of my course, then we have to be working at a different standard. You don’t see that at elite or even normal 4-year colleges, yet most of what you see out there that involves higher education deals with those students. There are some community college specific resources, but they don’t drive the national conversation about education.

As this report shows, that bottom level of college students are more likely to come out of school with few skills and few prospects, where the likelihood is that they “are more likely to be living at home with their parents, burdened by credit-card debt, unmarried, and unemployed.” And, that makes it more difficult to justify an education to the students and to justify the cost of that education to those who pay for it. Of course, as I have noted so many times, articles like this love to point out the problems, but they never say much of anything about solutions. In fact, the implication of the end of the article is that maybe this research isn’t really correct and that we need to do our own research to find out the real truth. But I see the failures every day. We know that a certain number of students will simply never make it through, no matter what we do. It is sad, but it is true. But are we giving value to the rest of the students is the real question. I hope that we are, and I know that our current assessment craze is trying to prove that. I guess I don’t have anything more profound than that to say about it. It is definitely one of those things that makes teaching hard and makes justifying the money and time spent on teaching hard. But the question to ask always is, would we prefer a system where we never give any but the top people a chance at an education?

I came across two other related articles on teaching that I thought I would talk about for the rest of this blog post:

Colleges looking beyond the lecture

I picked this one because it is one of the things that pisses me off over and over in reading articles about changes in teaching. Here’s the reason: “Science, math and engineering departments at many universities are abandoning or retooling the lecture as a style of teaching, worried that it’s driving students away.” Where are the humanities and social sciences in this? Why is it only STEM that is trying to make changes. Yes, I can find a few history sites out there, but overwhelmingly if you’re talking about changing up education or the use of technology, it comes back over and over to STEM as the place where changes come from. So, wonderful, colleges are looking beyond the lecture in these areas because students aren’t succeeding with the lecture. Does that mean the lecture is working elsewhere? Or is it because the lecture is such an expected part of other areas of education that we don’t even question its utility.

So, the article goes on to talk about the challenges of the lecture system — low student learning, the ability of students to get the same information elsewhere, and low retention. What is interesting is the last part of the article that talks about the solutions, which is mostly to stop lecturing. While they don’t use the term “flipping” the classroom in this article, that is what is discussed over and over. So, nothing really new over things I have discussed in the past. What is interesting is that most of the solutions talk about “experimental” classes that are tiny in comparison to the large lecture classes. But, is that an acceptable solution? Obviously, we have large classes because that’s what makes the most monetary sense, and we are not going to switch to a situation where there are no more big classes. So, I found the solutions here to be unrealistic.

At M.I.T., Large Lectures Are Going the Way of the Blackboard

This article is certainly related to the last, and I include it here, as this is the direction that everyone looking at education reform is looking at, based simply on how many articles there are out there. It is, of course, also what I am considering, which is why I pull every article like this out to look at more closely. But then, what do I see? “The physics department has replaced the traditional large introductory lecture with smaller classes that emphasize hands-on, interactive, collaborative learning.” Back to STEM. Back to ending the large classes. Sigh.

Of course, if we had the money and resources, I would certainly jump at trying this: “At M.I.T., two introductory courses are still required — classical mechanics and electromagnetism — but today they meet in high-tech classrooms, where about 80 students sit at 13 round tables equipped with networked computers. Instead of blackboards, the walls are covered with white boards and huge display screens. Circulating with a team of teaching assistants, the professor makes brief presentations of general principles and engages the students as they work out related concepts in small groups. Teachers and students conduct experiments together. The room buzzes. Conferring with tablemates, calling out questions and jumping up to write formulas on the white boards are all encouraged.” But, we don’t have that type of classroom, those types of rooms to work with, teaching assistants, or anything like that. Plus, as the first article made the distinction, is this something that only works with the top level of college students or could it work for the bottom as well? A big question that I do not know the answer to. But since this is where the current push to change the system is going, I am trying to find out all that I can.

That’s why I started with the first article, as I think that we do design and think about the top level of students first, but that often leaves the bottom level out. And, I teach a good portion of students who are at that bottom level. I am trying to change their opportunities, but so often it does seem like the solutions I’m looking at require more money, time, and resources than are available to me. And yet, we’re also facing continuous budget cuts because even at the level we are now, we seen as being too expensive. I don’t know what this means, but it does make the job more difficult. Being innovative, creative, and improving student success on the cheap is very difficult.

Thoughts on a Good Class – 2/14/2012 – A gratifying discussion

This week was my first experiment in something different in my classes. I have had discussion days before, so that was not the real difference here. What was different is that I had a day designed purely to explore a single topic in great detail with the students doing all of the preparation work outside of class and coming in simply to discuss that issue. In this case, I set up the material for the discussion by covering the three main tendrils of history that led into the topic — immigration, unionization, and Progressivism. Each of those had been covered in lecture in the days before this class, and so each student should have had a general idea of the historical context in which the incident took place.

In designing my “In-Class Activity” day, I had gone on the web to look at what resources were out there, as I wanted to give the students something that they would not access in a normal class. I did not want a traditional discussion where you have the students go out and read some primary sources and then come back and talk about them. I wanted something different, something that would engage the students in a different way, and yet accomplish the very goals that I always try to reach, having them connect the historical events to the modern age. As well, I wanted them to be confronted with an event that happened to people like them but 100 years earlier so that they could relate to them. Traditional “great man” history does not speak to them in many ways, but getting down to average Americans working hard just to get by speaks well to students, especially the non-traditional ones you find in a community college setting who have been out and worked in the real world.

What I had the students do was go out to the PBS website and watch the American Experience program on The Triangle Fire of 1911. They also were to access a couple of the other resources there, including an introductory essay, biographies of some of the participants, and a few informative pictures in a slideshow. The combination of that material was what they had to do before class, and it was open and available from the first day of class. To get into class on the day of the discussion, the students were required to bring a 1-2 page response to the material. I did not guide them in what they were to write specifically, but left it open to them as far as what they wrote.

It was an experiment in something new, and I really had no idea how it would go. Would they do the work ahead of time? Well, about 80-85% of the students who showed up brought a 1-2 page response. I did not let the rest stay in the class and told them to leave with a 0 for the day. Of those who had a response, I would estimate that about 10-15% of them really didn’t do much of the assigned work. On the other end, about 10-15% went well beyond the required viewings and did their own research. And, another 10-15% couldn’t get all of the resources to work for one reason or another. Of those, a gratifying few did go out and research on their own to find the information. One even told me that the same video was on Netflix streaming, which tells me I should check next time to offer that as a place for students to check.

The next question is, would they engage the material and have something to say about it? I say it was an unmitigated success in this regard. I began the discussion with the most general question possible, “What did you think about the video?” In both of the discussions I’ve had so far, people stopped having a response to that question after about 30 minutes. So, we had 30 minutes of discussion, with me saying quite little except for guiding who would speak next, on just a response to the video. I took notes during that time and did the rest of the discussion off of the topics that they brought up the most. We easily filled the rest of the class period (75 minutes total) with no problems and very few gaps where nobody had anything to say. Of course, some of that is because they were being graded on the discussion, but they really were responding well to the material and had a lot to say at all parts of the discussion. In both classes, I have the feeling that we could have filled much more time if we had it, but that we really did dissect the issues at the time well, while also relating the experiences from that time to the modern day well. I also get the feeling from the responses that I heard that they will remember this event and the discussion we had about it much longer than they probably will the individual things that I lecture on each day.

What do I take away from this? I consider it an overwhelming success on a thing that I wasn’t sure would work. The response was excellent, and students did the work ahead of time, which was something I was very worried about. But why did it work so well? I think some of it has to do with the form of media. There’s something about watching a documentary, especially when you can watch it on your own time rather than being forced to sit there in class and watch it that can be quite engaging. This was a very well done one, which does help as well. Also, it is not “traditional” history. One of the first responses I got, before I even really started the discussion was that almost all of the students had no knowledge of the incident before. They had never heard of it, but they were interested in it. The subject reflects on topics that are relevant in the lives of people who would be at a community college, in that it is primarily about working-age people, mostly women, who are struggling in a system that seems set up against them. The students brought up personal experiences a number of times as they attempted to relate what they had seen there to their own lives, and I did not have to guide them to do this. In fact, I like that word guide, as I felt much more like I was just a guide in the discussion then that I was a leader of the discussion.

I have one more section that will do the discussion tomorrow, and I hope it goes just as well. It’s days and assignments like this that energize me as a teacher and keep me going as an educator.

Thoughts on History – 2/13/2012 – State of the Field

Two articles were delivered into my email yesterday on the state of the field of history. So, I thought I would write about them, having gone through the dissertation process myself (without completing it) and teaching history now. I certainly have my own opinions, and I’m sure that will come through here.

What’s Been Lost in History (As a note, I got this off of some place that allows me to read the full article. You have to have a subscription to read it on the Chronicle’s site.)

This is a fairly common-sense recounting of the problems with the job market for people pursuing a Ph.D. in history. He notes that the typical history department prepares students for a single profession, that of being a professor in a tenure-track job, doing research and a bit of teaching as necessary. If you do not aspire to that, the current state of history graduate education is not designed for you. While I did not go through the program looking for a nonacademic job, as this article focuses on, I still was an outsider, as I quickly discovered that I was much more interested in teaching than research. In fact, I spent 5 1/2 years in a Ph.D. program trying to convince myself that I could do enough of the research side of things to get through with the Ph.D. and hopefully get a teaching job somewhere. In the end, I left with a good amount of teaching experience, so I am thankful for that, but the emphasis on producing researchers was undoubtedly the only acceptable focus in my experience, just as this article discusses. As he says, “I do not have solid evidence on this point, but I think the notion of academe as the only suitable outcome of doctoral education is a myth generated by the highly untypical period from the mid-1950s to about 1970. My sense is that the historical profession (and the human sciences generally) became much narrower and more academic in the decades after World War II.” I think it is stuck in a rut, just as I’ve been talking about with other aspects of teaching in this blog so far. Why do we get taught this way in doctoral programs, because that’s the way they were taught. We even talked about the comprehensive exams as an archaic hazing ritual, done because that’s what our professors had to do.

His solution is to make the history degree more of a “pre-professional degree” than just one that leads to an academic research career. Acknowledge that many people who go into history will get a law degree or a museum placement or (like me) a teaching job. He advocates linking up history with “public affairs, business administration, international relations, social work, and journalism” as well, which would strengthen historical thinking and reasoning across the professions. Make it into something that people have more options with. When I left my undergraduate institution with a degree in history, I never got any real guidance on what I could do outside of going to grad school. Nobody ever talked about other options, and I went to grad school largely because I really didn’t know what else to do. There were no real connections to other fields, outside of one class that was only tangentially connected to the history department that looked at public history. I also got an internship at a museum in the summer before my senior year, but it also never really led to anything. All paths pointed to grad school, with no real alternatives given. So, there I went. And there was a very focused program with little ideas outside of research.

As he says, “Doctoral training in history as it developed in the 19th century included a commitment to civic life and leadership; in the first half of the 20th century, history was at the core of civic professionalism, partly because the social sciences generally were then historicist.” I will go even further to say that it is not just doctoral history, but history at all levels. This is something that I have been struggling with here in this blog because it has to do with the relevance of the subject that I teach directly. Is history just the memorization of facts at the undergraduate level or the research of some minutia that somebody else hasn’t found yet at the graduate level? I hope that it is more than that, and I like the civic aspects and the preparation for other careers that are discussed as alternatives in this article.

I guess that the more I look back on it, the more disappointed I am in my undergraduate and graduate education in preparing me for what I am actually doing now. Perhaps that means I was not suited to do history as I did, but I love teaching it, and I’m not sure how else I could have gone through the process without getting the teaching experience ahead of time to be able to get the job I did get. It just seems somewhat hollow when I look back on it. One of my friends in grad school said it best — everything he wanted to do in history you could do without a Ph.D., while everything you did to get a Ph.D. in history was not anything he wanted to do. Yet, idealistic people keep going in, with the hope that they will be the ones to buck the system. Hopefully one of them succeeds, but for now, I will try to do my best from a lower rung in the academic ladder.

Coming out of the American Historical Association (I should probably join this again at some point) is apparently a new effort to define what it means to get a history degree at the “associate, bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral” levels. Right now, there is no definition of that at all, and each institution’s degree is fundamentally different from each other one (I might even argue that each student’s experience in each program is fundamentally different). Of course, at my community college, you can’t even get an associate degree in history at all, so that’s a fascinating concept in and of itself. And, most importantly, this effort will not be about what is taught (the specifics), but about the competencies that one would expect to come out of a degree in history. In other words, this is another in the line of the assessment push now. It will be interesting to see how this turns out. Is it going to be a hollow change that ends up not meaning much, or will it provide some legitimacy and direction, much as was discussed in the previous article.

I don’t know that anything that I saw here will fundamentally change what I’m doing in the classroom, and it was interesting to see that the competencies here were basically the exact things that I already try to emphasize. But some commonalities would be good, especially if you could combine what was in this article with the previous one. I do think it would be even more valuable at the higher levels, as the graduate level is often even more amorphous. Some structure and variety in instructional ideas and techniques could have the potential to bring about changes. I guess I’m less optimistic there, but you would hope that things would change at some point to open up a field that is so singularly focused.

Thoughts on Education – 2/12/2012 – Is Technology the Solution?

I haven’t had much time to sit down and think about education since Thursday. It’s funny how the weekends slip away from you. I do have a big backlog of articles after having not done them on either Thursday or Friday, so I’m going to stick with more reviews today. I haven’t quite figured out what’s a good mix here, more of my own stuff or more article reviews. Of course, even in the article reviews, I am including a lot of my own thoughts as well. Right now, I’m doing article reviews when I get 4-5 articles I want to look at. However, I do look at so many places for information through the week, that it is honestly quite hard not to have that many articles to examine.

Using Technology to Learn More Efficiently

OK, so to start, just ignore the large Jessica Simpson lookalike on the page there, as distracting as her stare is there. I was interested in the article from the title, which is what gets me to save most of them for review later. So, often as I’m sitting down here to write about them, I am reading them for the first time as well. Sometimes they are so irrelevant or don’t do what I want that I simply don’t do anything with them at all, such as this one today. This one almost got a delete as well, but the concept is at least interesting, even if it links up to an older style of learning that I don’t want to encourage in my own classroom — flash cards. The article profiles a company that is digitizing flash cards and remaking them to encourage better retention and more honest use of flash cards. The more compelling idea is the creation of a schedule and the push for accountability to the students to complete their work. As the article notes, this is really an attempt to reduce the unproductive cramming before an exam and open up a broader studying schedule. However, the ultimate limitation here is the students. They are the ones who have to make the decision not to cram at the last minute, and I have a feeling that the students who would do this with this program would be the same ones who would be least likely to put off all of their learning to the last minute anyway. Still, I’m all for accountability, especially if it could be integrated with that idea from yesterday on using Google Docs to gauge student progress. So, maybe as a tool that an instructor could put together and release to the student, this could work.

The Gamified Classroom (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4)

“Today, students are expected to pay attention and learn in an environment that is completely foreign to them. In their personal time they are active participants with the information they consume; whether it be video games or working on their Facebook profile, students spend their free time contributing to, and feeling engaged by, a larger system. Yet in the classroom setting, the majority of teachers will still expect students to sit there and listen attentively, occasionally answering a question after quietly raising their hand. Is it any wonder that students don’t feel engaged by their classwork?”

This, again, goes back to the issues I’ve talked about in several other posts, especially the last one. If we are talking about student engagement, then I think we are failing with the lecture model, especially to the most current generation of students, which is who this article series concerns. I just have to look out at my own classes on lecture days to see the problems, with maybe 1/3 paying active attention, 1/3 paying occasional attention, and 1/3 completely disengaged from the material. Of course, is gamification the answer? Of course not. But can we learn something from this educational trend? Very likely. Perhaps it can bring in greater engagement and even foster creativity rather than rote learning.

The role of technology can both help and hinder learning. The article refers to a number of ways that technology can help engagement, through having the students involved in project based learning and higher levels of engagement, using both apps and clickers. What is interesting is what the author sees as one way that technology is reducing that engagement as well, the smartboard. I’ve not seen that criticism before, as the smartboard is often held up as one of the prime ways to engage students. “Unfortunately, our classroom is often filled with technology that only exists to better enable old styles of teaching, the biggest culprit being the smartboard. Though it has a veneer of interactivity, smartboards serve only as a conduit for lecture based learning. They sit in front of an entire classroom and allow a teacher to present un-differentiated material to the entire group. Even their “interactive” capabilities serve only the student called upon to represent the class at the board.” I have been suspicious of smartboards as a save-all, but I had never really been able to figure out why I didn’t like them. I find this argument compelling. From my own point of view, they seem to just be a new version of the chalk board, offering nothing more than you can find with the method.

“In schools, our students should be using technology to collaborate together on projects, present their ideas to their peers, research information quickly, or to hone the countless other skills that they will need in the 21st century workplace–regardless of the hardware they will be using in the future. If we’re just using tech to teach them the same old lessons. . . we’re wasting its potential. Students are already using these skills when they blog, post a video to YouTube, or edit a wiki about their favorite video game. They already have these skills; we have to show them how to use them productively and not just for entertainment. This is where Gamification comes in. Games are an important piece of the puzzle–they are how we get students interested in using these tools in the classroom environment.” I agree. Ha! What I always tell my students not to do, present a big quotation and say they agree, but I guess I’ll hold myself to a lower standard than them. Still, I think this is an insightful look at the problems with just throwing technology at the problem. You can’t just hand teachers technology and expect them to transform everything. Technology is not the solution, although effective teaching with effective technology could be part of the solution.

The last two Parts of the series deal with how this might take place in practice. I’m not going to go through all of that here, as the information is diverse and hard to summarize. So, check it out if you’re interested. I think what is most interesting is the push for self-pacing and self-motivation for students. Tying completion to rewards beyond simple grades and pushing the students to do more. This is an interesting idea, but I do wonder if our students are ready for this. That is always the problem with these articles, that they project these things into an ideal world where students are not motivated because we aren’t motivating them. Yet, the real problem is often much more complex. Our students are as varied as can be, and the reasons for motivation or lack of motivation are varied in the same way. How do you motivate students who are working two jobs, taking care of kids, sick, taking care of sick family members, in school only because their parents think they should, in school only because they think the should, and so forth. In other words, when students aren’t required to be there, such as at college, how does this push differ? Something to think about.

The loss of solitude in schools

And, I’ll close for today with an opposite view. Here, the author is warning against the push for project-centered education, one where we emphasize interaction and group work over individual absorption of material. She makes the case that education is inherently a solitary process, where we engage with and absorb difficult material until we learn it. As she says, the emphasis on group work and interaction produces students that “become dependent on small-group activity and intolerant of extended presentations, quiet work, or whole-class discussions.” In other words, they forget how to learn on their own.

She also notes that the push away from the “sage on the stage” can be just as damaging for students. “Students need their sages; they need teachers who actually teach, and they need something to take in. A teacher who knows the subject and presents it well can give students something to carry in their minds.” I have never done much with small group work, so I can’t say one way or another how this works. I have generally done either lecture or discussions. I don’t know how to evaluate small group work, and so I have not done it. Perhaps this is short-sighted of me, but I just don’t know how to give a grade for group work that is not just on the end project. In other words, how do you hold everyone accountable? I know, from talking with my wife and remembering my own experiences, that group work is inherently unequal and very frustrating for those who want to do a good job, as they generally end up doing most of it. I don’t want to put students in that position, and have never been much for this idea. I could be convinced otherwise, but I am skeptical on the idea of small group work. I know that many of the changes I’m looking at making involve small group work, but I just don’t know what to do with it.

Anyway, enough for today. Please let me know what you think or if you have any responses to the ideas I’m presenting, as I don’t want to be working in a vacuum on this.