Thoughts on Education – 4/29/2012 – Technology in the classroom – iPads and more

I have been saving up quite a few articles over my inactive time the last month or so, and today I want to turn to a couple that address technology in the classroom. Technology is often presented as the cure-all for education, and I will admit as much guilt as far as this goes as anyone else. I am always out looking for the new piece of technology (although often I can’t afford it), and I will often then sit down and think about how I could use it in the classroom. Unfortunately, a lot of what I would like to do with technology, namely engage the students more directly, would be difficult without all of the students having the same access to the same technology. This can be fixed through things like classroom sets of technology instruments, but that is an inelegant solution at best.

We have done several of those things at my community college in the past and present. A couple of years ago, we acquired a couple of sets of clickers, when that was seen as the latest tool for attracting student interest. We also had a push for getting online classes to think about using Second Life for a short period of time. Both of those technologies seemed limited and untried at the time, and I never found any interest in adopting them. Neither went far at the college, although I do think we have a couple of people still using clickers, and we do teach some of our gaming in Second Life. The question of the day on this topic is, of course, iPads. They are the latest thing, and I am part of a faculty workgroup that has gotten iPads as a test piece for our own educational use as well as overseeing the deployment and use of classroom sets of iPads. The question will be if this is another short-spike-of-interest device or if it has a long shelf life in education.

The latter option is reflected in this article, titled “How the iPad is Changing Education.” Although the article is more speculative than directly tied to evidence (probably because of the short time these devices have been really available), the article does point to some increase in learning and success among students using iPads. Of more interest is this point: “In the meantime, the devices make a great tool for self-directed, independent learning. There’s no shortage of one-off educational apps on any given subject, from American History to advanced biology.” Of course, this requires engaged students, and use outside of a classroom set (or time set aside in class to use the iPads for this purpose). Still, that is certainly what I have found as I have looked around for possible apps for use in the classroom myself. I can find dozens of whiteboard and projection apps, but the actual learning apps for the classroom are scarce. However, from teaching American history, I can certainly vouch for the number of American history apps out there, most of them informative and of very uneven quality. Few have much in the way of classroom application, although I have found a few. So, the iPad, as it stands right now is much more an information-retreival device than an active-use device in the classroom. As the article notes at the end, the real strength of the iPad for classroom use comes in the ability to make your own books and access iTunes U. As those areas develop more, there might be some possible in-class uses for them, but they still remain mostly passive presenters of information. I’ll be curious when the first truly in-class, adaptive, learning app comes along. Has anyone found one yet?

As this article notes, the issue is also not just what you can access through a device like the iPad, but also how the iPad is used. If it is used, as I noted above, as a substitute textbook, then that’s all it is. The students will ignore it just as they ignore the current textbooks today. This is my greatest fear of our adoption, that we will not find enough content out there and not have enough time ourselves to develop new, and the iPads will end as just a fancy way to access content, leaving it relatively unnecessary. It will then be a neat trick, and not much more. This article comes back to the whiteboard idea again. We will have a new academic building where our iPads are going to key into Apple TVs in the room and hopefully be able to interact with smart boards. I might get more use out of the iPad as a teaching tool, and whiteboarding might be a good way to get students working with each other. We shall see.

However, without the new building, I have been struggling to figure out how to use this new technology in the classroom. That’s why this title caught my attention – “Five Ways to Bring High-Tech Ideas into Low-Tech Classrooms” These ideas are interesting enough to detail a bit here:

- Put the Facebook page on paper – Start up something that the students can use as a reading log or something like that. Basically, it’s a way to create a live blog of material going on in the classroom and outside. The students can see each other’s blogs and like them. Status updates, posting of pictures, linking, etc. can all take place. This is the most promising use of the iPad in the classroom that I have come across, as a platform to extend what is going on outside of class into the classroom as well.

- Build a classroom search engine – less interesting to me because I tried this before. I started using wikis to create a classroom definition bank starting about 4 years ago. I never was able to use it with any real success, but it might be useful someday for something like this.

- Tweet to Learn – OK. I don’t use Twitter. I probably should, but I don’t. Why should I? You tell me how it could be useful in a classroom situation.

- Encourage students to “chat” – an in-class chatroom is something I’ve been toying with for a while. Maybe this coming semester, as part of my broader changes.

- Talk the Text Talk – OK. No. Not going to do this, especially not in college

Anyway, I thought those ideas were interesting enough as part of what we could all be doing more of. I’m also getting a bit more desperate about how I’m going to use the iPads in the classroom. The college has spent quite a bit of money to get me one and have several classroom sets. I’m just afraid I don’t know what to do with them, and so I’m trying to think about it more and more.

As a side note, I start the final grading push for the semester tomorrow, so I may not be very regular here for a while. We close on our house this Friday as well, so that will also bring a whole new set of obligations.

Thoughts on Education – 04/28/2012 – Mentoring college students

I went up to campus yesterday on my day off to a meeting centered around a new push to mentor our students. I have been on our college’s retention committee for two years now, and we are starting to see some of our ideas floating up through the bureaucracy of the college and becoming an actual part of what we do. Some of the changes so far have been with regard to easing registration, requiring students to visit their instructors to get drop slips signed, introducing a small set of students to a “how to do college” class, and so forth. The faculty side of things has largely been left out of the changes so far, but one of the things that I have been pushing for is starting to come into existence. I believe that students should have actual faculty advisors that they talk to, not for setting up schedules, but for more general college advice and help making it through the college process. Thus, we now have the beginning of a mentoring program. It will be slowly launched in a pilot program this fall, and the meeting yesterday was the first in a series of meetings to gain interest and see who would be willing to use their time for this.

The program itself, from what I understand, will be aimed fairly narrowly at first. We will be advising first-time-in-college, first-semester, full-time students. Out of our 5000 or so students, that means about 3-400 students that we will be directly mentoring in this first batch. I fully applaud this idea. I would love to see it expanded soon, but I know that it has to start somewhere. As the program sits now, we will be given 5-10 of these students to mentor, with the expectation that we will try to meet with them around three times a semester, serving as a person they can talk to about college, get advice from, and use as a sounding board. These are students who need all the help they can get, but, honestly, there’s probably not a single student on campus who could not use some set of advice.

This was echoed in this article from the Chronicle recently. In it, community colleges are admonished to stop blaming others for the problems of students not succeeding and doing what they can internally to improve this. I think the retention work we have been doing, and this mentoring program as a part of it, is a good step along the way toward creating better chances for success among our students. As well, the second point from the article is also part of this. She says that colleges, especially community colleges, need to be better at guiding students through the process. Right now, our students, without a serious amount of advice outside of preparing schedules each semester, blunder forward until they have reached enough credits to do something with them. For many, the idea of a degree plan, a goal outside of taking their “basics,” or even what it takes to graduate, is something that only the most academically involved and prepared students have. A mentoring program can help focus the students in on their plans and help with general academic planning throughout their career. If we can get them in, out, and done, we will be succeeding. The longer they take, the more likely they are to not succeed. As well, the less focused they are, the less likely they are to reach a satisfactory conclusion to their academic career. Hopefully this mentoring program can get them going with that.

Programs like this are also an answer to the question of how we measure student progress. Right now, we are in this wave of measuring, one that looks at the progress that students make academically as they proceed through college. This article from The New York Times illustrates that, discussing the need for something that can measure progress and pointing out the different ways this is currently done. I think an equally valid measure is what success the students have in reaching their goals, regardless of specific success in a specific course. With a mentoring and advising program, that can be helped, as we can work with students who are often lacking in a real idea of what they want to do. This group we will be dealing with is especially unconnected to the traditional measures of success and progress, as they have no family experience to fall back on as to what they should be doing in college. What they know is that they are supposed to go to college to get something (often undefined) and that by taking classes they will somehow get there. I know we are not the first place to ever put in place an advising program, and I know that success with the program will depend on both instructor and student participation. However, if we can even point half of these students in a more productive direction, then we will have success. If they can come out with a better idea of what they need to be doing, what classes will get them there, and what they can do with the classes/degree afterwards, then we will have helped them along the way.

Thoughts on Education – 3/18/2012 – Comparing 5th graders to college students

My fifth grade boys brought home an interesting assignment on Monday. They had to write an outline for a “research” paper that they are working on. They had to pick a topic and then write a thesis statement. They had to put it all into the standard 5-paragraph essay format, putting in topic sentences for each paragraph and then listing 3 details they were going to put in each paragraph. What was interesting about that is that they really did not have a strong grasp on what a thesis statement was or how to put together the paragraphs. I saw the instructions that the teacher gave them, and it’s not like they hadn’t been taught this to a certain extent, but the boys obviously had not fully grasped it.

So, we had to have some work time on Monday on what a thesis statement is. Since these are fairly simple research papers (topics = muscle cars for one and puffins for the other), we had to start pretty basic. I had them think about why they wanted to write on those topics and then come up with three reasons for each one. So, the why they wanted to talk about the topic became their thesis, and the three reasons formed the body paragraphs. While that sounds pretty simple, it was actually a pretty long and agonizing discussion, as they had not really thought about why they had picked their topic, outside of the fact that it seemed cool. So, we had to work on some reasoning skills and delve down below the level of cool and into the reasons behind cool. It took quite a while, and one of the boys did have a short crying fit over frustration at not being able to articulate his reasons. However, we ultimately prevailed, and they were able to put together their ideas into the format that was desired.

What was interesting about that, is that we put more thought into how they were going to go about thinking and writing this paper than I think a lot of my own students do. They have just as much trouble with the idea of a thesis statement and presenting evidence, which makes me think that my 5th graders are not alone in not fully understanding this concept at this level. In fact, it seems to me that this is a concept that gets lost all the way through, as there really is no excuse for my college freshmen and sophomores to be having trouble writing a coherent thesis statement and using evidence if they are supposed to start learning about this all the way back to elementary school.

As I said, though, it was very obvious that even though my 5th graders had been taught generally how to do it, it took us a long time to translate that into a practical and working thesis and essay outline. So, maybe it is just assumed along the way that they have learned this before, when maybe they really have not.

The whole process has made me think about assumptions. I assume a lot about what the students I teach have had as a background before entering my class. As this example shows, however, just because someone is taught something, that does not mean they actually understand it. I think this is certainly a lesson that all of us in education need to consider on a regular basis.

Thoughts on Education – 3/28/2012 – Thinking about the future of education

I haven’t done any article reviews in a while, so I thought I’d sit down and hit my Evernote box a bit here. So, here we go.

The first article comes from the ProfHacker blog at the Chronicle of Higher Ed. As with so many others, the intent here is to look at way the future of the university system will be, and while I teach at a community college, and not a university, the ideas are still relevant. I also, of course, like the origin of this one, since it came out of a conference at my alma mater, Rice University. It starts off this way: “I sometimes hear that the classroom of today looks and functions much like the classroom of the 19th century—desks lined up in neat rows, facing the central authority of the teacher and a chalkboard (or, for a contemporary twist, a whiteboard or screen.) Is this model, born of the industrial age, the best way to meet the educational challenges of the future? What do we see as the college classroom of the future: a studio? a reconfigurable space with flexible seating and no center stage? virtual collaborative spaces, with learners connected via their own devices?” Certainly, my classrooms are set up that way, even my “other” classroom, the two-way video one, still has all of the emphasis on me. The article also noted: “With declining state support, tuition costs are rising, placing a college education further out of reach for many people. Amy Gutmann presented figures showing that wealthy students are vastly over-represented at elite institutions even when controlling for qualifications. According to Rawlings, higher education is now perceived as a “private interest” rather than a public good. With mounting economic pressures, the public views the purpose of college as career preparation rather than as shaping educated citizens. In addition, studies such as Academically Adrift have raised concerns that students don’t learn much in college.” I have posted up articles that talk about both of those things before, but this information from this conference really narrows it all down well. At its heart, what the article notes from the conference is that it is time to update the model to the Digital Age from our older Industrial Age. That we have adopted the multiple-choice exam and the emphasis on paying attention in class from this old Industrial model, where creating a standardized and regulated labor force was key. In the Digital Age, it will be important to “ensure that kids know how to code (and thus understand how technical systems work), enable students to take control of their own learning (such as by helping to design the syllabus and to lead the class), and devise more nuanced, flexible, peer-driven assessments.” Throughout the conference, apparently, the emphasis was on “hacking” education, overturning our assumptions, and trying something new. While the solutions are general in nature, I found this summary of the conference to be right up my alley, and certainly a part of my own thinking as I redesign. I wish I had known about the conference, as I would have loved to have attended.

Looking at the question from the opposite end is this article from The Choice blog at The New York Times. The blog post was in response to the UnCollege movement, that says that college is not a place where real learning occurs and that students would be better off not going to college and just going out and pursuing their own dreams and desires without the burden of a college education. What is presented here is some of the responses to that idea. A number of people wrote in talking about what the value of college is, so this gives some good baseline information on what college is seen as valuable for. Here are some of them:

- “a college degree is economically valuable”

- “college is a fertile environment for developing critical reasoning skills”

- several noted that you can get a self-directed, practical college education if you want it

- “opting out is generally not realistic or responsible, given the market value of a degree”

- “the true value of college is ineffable and ‘deeply personal,’ not fully measurable in quantifiable ways like test scores and salaries”

That’s just some of the responses, specifically the positive ones, as that’s what I’m looking at here. It is interesting to see the mix of practical things and more esoteric ideas. I think that both are hopefully a part of college education and that both are part of what we deliver. I would like to think that’s what my students are getting out of college in general, and I hope that the redesign that I am going for will help foster that even more. I especially hope to bring more of the second and fifth comments into what I am doing, as that is the side that I think a college history class can help with.

Then there is this rather disturbing article, again from The Chronicle of Higher Ed. It discusses the rising push for more and more online courses, especially at the community college level. As the article notes, that is often at the center of the debate over how to grant a higher level of access to the education experience for more and more people. But, with more emphasis being put on the graduation or completion end and less on the how many are enrolled end, this could end up putting community colleges at an even higher disadvantage. As one recent study put it, “‘Regardless of their initial level of preparation … students were more likely to fail or withdraw from online courses than from face-to-face courses. In addition, students who took online coursework in early semesters were slightly less likely to return to school in subsequent semesters, and students who took a higher proportion of credits online were slightly less likely to attain an educational award or transfer to a four-year institution.'” So, we are actually putting our students into more online classes that make them less likely to finish overall. In fact, they are not only less likely to finish, but they are less likely to succeed at that specific class or come back for later classes. As well, a different study pointed out similar problems for online students: “‘While advocates argue that online learning is a promising means to increase access to college and to improve student progression through higher-education programs, the Department of Education report does not present evidence that fully online delivery produces superior learning outcomes for typical college courses, particularly among low-income and academically underprepared students. Indeed some evidence beyond the meta-analysis suggests that, without additional supports, online learning may even undercut progression among low-income and academically underprepared students.'” This is disturbing to me, as this is exactly what I teach at least half of my schedule each semester in – the online environment exclusively. I know that success in an online class is difficult, although I have actually been slowly improving the success rate over time in my online sections. I think I’ve finally hit a good sweet spot with the online classes right now, and I’m less in need of fixing them at the moment. I do, however, agree with the very end of the article that says that what is often missing from the online courses is the “personal touch.” That is the only part of the class that I would like to change, as I need a way for me to be more active in the class right now. I can direct from the point of putting in Announcements and the like, but I do feel that I get lost in whatever the day to day activities are. I need to design some part of the class that has me participating more directly rather than leaving it up to the students. Otherwise, I do think I’m doing pretty well in this part of my teaching career.

OK. I think I’m going to call it a night here. Any reactions?

Thoughts on Teaching – 3/27/2012 – Dropping classes

This was a banner day for dropping my class today. That is probably because the next big round of assignments is coming due in the next week or so, and people are getting out now before they have to put in any more actual work. I signed drop slips for 4 students today. That’s certainly not a record by any means, but it is always interesting that they come in waves like that. I had three come to me either right before or after class, and since my Tuesday/Thursday class is the worst one this semester, in terms of grades at least, that is really no surprise. What is more surprising are the other two who came by my office. Two different students came by with progress report sheets to fill out, and I had to break it to both that they were doing very poorly in the class. Both of them knew that generally, but the numbers are much harsher. Of the two, one decided to drop, and the other stayed in. With both, they had skipped a significant portion of the assignments due so far, so they should not have been really surprised about it. Still, they were, as I think that students often don’t think that much about the effects of their actions on their class grade.

The good thing about the drops and discussions of progress today was that all of them took responsibility for their poor performance. I didn’t have any who blamed anything that I was doing in the class, which is really always a relief. I don’t know about any other teachers out there, but I am always incredibly nervous and self-conscious about my teaching and whether I am giving the students everything they need to succeed. I see a failure by a student as a personal failure on my part quite often. I always wonder if there’s something else that I could have done for them. So, when they come to me and talk about what they did wrong in the course, it always is a bit of a relief – guilty relief – but still relief. I don’t know if it is just my personality or if it is something every teacher feels, but I get very personally invested in my students. It’s one of those things that does make this job exhausting at times, as I take even a rough comment or criticism as a personal attack on my teaching skills and I fret over it for a long time. But a day like today, while upsetting because so many dropped, is somewhat of a relief, as I got some personal validation that I was not directly to blame for any of these. Isn’t it strange how the mind works? I assume things with my students are my fault until proven otherwise. Any other teachers out there have this same feeling?

Anyway, just a few thoughts to end a very long day.

Thoughts on Education – 3/22/2102 – My first webinar

So, I had the opportunity on Tuesday to lead my first webinar. It is not something that I have done before, and it was an interesting new experience. I was working with McGraw-Hill for this one, helping them demonstrate Connect History to faculty members around the US. I can’t say we had a huge turnout, as there were only 4 faculty members on the webinar, although we had about twice as many McGraw-Hill employees there as well. My job was to talk for about 20 minutes and demonstrate how I use the Connect History platform. I was sharing my desktop in the process, so that the people there could see what I do with Connect History in my classroom. Then, I took questions for the rest of the time. As I said above, it was an interesting experience. I have participated in webinars before, but it was my first time leading one. It was not a particularly difficult thing to do, as it naturally feeds from the experience that we have as instructors anyway. It is just a different thing, as you are there with no direct audience, talking to a computer screen without being able to see anyone else. I do feel that I effectively communicated what I was supposed to, and I think the participants were satisfied (all except one who would never be satisfied, from what I can tell).

In a broader sense, the webinar format certainly makes me think about delivery of material online in general. I can’t help but think that some format like this would be great for an online course. The only problem is that it really does require everyone to be on at the same time to get the basic interaction down. Otherwise, you are just working with a static delivery of material anyway. If you could commit your students to being online all at a certain time to hear you lecture or discuss, you could do a lot and not take up classroom space at the same time. It is an interesting idea, scheduling an online course to take place at a certain time, even well outside the normal times that we would meet face-to-face. Certainly this does not get me past the lecture, as I have been talking about here, but I can’t help but see a more personalized experience like this being much better than the required time that a student has to come and sit in class. Of course, I would still be requiring the students to be there at a certain time anyway. I wonder about a running discussion or something like that, where students could come and go over the course of hours, and I would just be there to moderate and guide for that time. I wonder if that would be more effective that the old standby of a discussion forum.

What do you think? Have you taken any webinars? What do you think of the format? Could we do something like this as teachers and enhance/change the online experience?

Thoughts on Education – 3/20/2012 – A long article

I promised that I would return to this article, and so I will here. I had read it earlier and just revisited it now. I was quite impressed with the thought that went into the article, and I found myself agreeing with a lot of what he said. I especially liked these ideas here:

- “Instructors walk to the front of rooms, large and small, assuming that their charges have come to class “prepared,” i.e. having done the reading that’s been assigned to them — occasionally online, but usually in hard copy of some kind. Some may actually have done that reading. And some may actually do it, after a fashion, before the next paper or exam (even though, as often as not, they will attempt to get by without having done so fully or at all). But the majority? On any given day?”

- “We want them to see the relevance of history in their own lives, even as we want them to understand and respect the pastness of the past. We want them to evaluate sources in terms of the information they reveal, the credibility they have or lack, or the questions they prompt. We want them to become independent-minded people capable of striking out on their own. In essence, we want for them what all teachers want: citizens who know how to read, write, and think.”

- “We think it’s our job to ask students to think like historians (historians, who, for the moment, were all born and trained in the twentieth century). We don’t really consider it our job to think like students as a means of showing them why someone would want to think like a historian. We take that for granted because it’s the choicewe made. Big mistake.”

- “For one thing, there’s too much “material” to “cover” (as if history must — can — be taught sequentially, or as if what’s covered in a lecture or a night’s reading is likely to be remembered beyond those eight magic words a student always longs to to be told: “what we need to know for the test”). For another, few teachers are trained and/or given time to develop curriculum beyond a specific departmental, school, or government mandate. The idea that educators would break with a core model of information delivery that dates back beyond the time of Horace Mann, and that the stuff of history would consist of improvisation, group work, and telling stories with sounds or pictures: we’ve entered a realm of fantasy (or, as far as some traditionalists may be concerned, a nightmare). College teachers in particular may well think of such an approach as beneath them: they’re scholars, not performers.”

- “Already, so much of history education, from middle school through college, is a matter of going through the motions.”

- “Can you be a student of history without reading? Yes, because it happens every day. Can you be a serious student of history, can you do history at the varsity level, without it? Probably not. But you can’t get from one to the other without recognizing, and acting, on the reality of student life as it is currently lived. That means imagining a world without books — broadly construed — as a means toward preventing their disappearance.”

OK, so if you’ve stuck with me this far, you are looking for more than just a bland repeating of what someone else said. So, here are my own thoughts on the matter. I think this is spot on with regard to the assumptions that we make in teaching history. I have long since given up on the idea that my students actually do the reading that I assign, although I do my damnedest to get them to. I put together more and more complex quizzes that the students have to complete on each chapter, with the hope that they will not be able to complete them without reading the chapters. Actually, I won’t even say I do that, as more of the approach I make is that it will be much easier and faster for the students to complete the assignments they are required to do if they have actually done the reading. What is funny, and really a failing on my part, is that I still run the class as if they are doing the reading, even though I know they don’t. This is exactly the fault at which this article is aimed.

I also fall victim to the idea of coverage. I feel that, as long as I am lecturing, then I am expected to fully cover the material for the course, telling the students everything that they are supposed to know. I adopt that “sage on the stage” persona so easily that it is scary. All it takes is for me to stand up in front of the class, and I can talk for 75-minutes on the subject, never asking questions, never stopping for clarifications, and just going, going, going. I do that day after day without really trying. Despite my best intentions, I have the standard lecture class down pat, so much so that it takes very little preparation on my part these days to be able to walk in and deliver that lecture. I wish this wasn’t so, but I feel that I’ve actually gotten lazy with my teaching, just delivering the same old series of lectures, which are now on their 4th year since the last set of revisions. I’m no better than that joke that we all laugh about of the old professor going in with his old hand-written notes on a legal pad that he did 20 years earlier and delivering the same lecture. I have fallen into that trap. Instead of innovating in the place where it matters most, I am stagnating. I have innovated everywhere else, but day in and day out, I do the same old thing.

So, what can I do? Well, I have already been planning it out in this blog, and the more I read things like this article, the more I am convinced that it is time for a radical change. I don’t mean incremental change with some modifications to the lecture and so forth. I mean radical change. Blowing up the lecture class. Flipping the classroom. Whatever you want to call it. I need to approach the students and deliver to them, not do what I and my colleagues have always done. And when I step down from my teaching high each day, I look around at the students, and what do I see? They are gazing off into the distance, texting on their phones, watching me, surfing the internet, taking notes, dozing, and all sorts of things. Yet, all of those things are passive. Sitting there. Letting themselves either be entertained or annoyed at having to be there (as if I’m forcing them to get a college education). I want an active classroom. I want the students to be engaged. I want to teach history, historical thinking, critical thinking, and so much more. I don’t want to just lecture, deliver. To do that, I’m going to have to step out of my comfort zone. I’m going to have to stop going in with my pre-made lecture and talk for 75 minutes. I will have to do it all differently. I will have to change. It will be hard. It will be a lot of work. It will be uncertain. But I hope it will also be valuable to my students and to me.

Thoughts on Education – 3/15/2012 – What is college for?

I can’t help but start today with a response to an article that I discussed in my last education post. The original article had students talking about what they didn’t like about the lecture format. This one has professors responding. I will be honest that the professor responses are quite underwhelming in my opinion. I don’t know if it is a result of editing that makes the professors less compelling than the students or what. In fact, the best response that I saw there was in the form of a PowerPoint, but the editing of the video made it impossible to read the PowerPoint fully in the time allotted for it. However, when paused, the best points are there, and they largely mirror the ones that I would make. That is, the the failure of lecture is the fault of both the instructor and the student. Since the fault of the instructor has already been raised, I’ll focus on the student side. Students are raised in our educational culture to see education as both something they will be guaranteed basic success at with not that much effort and as something that is a nuisance and waste of time. That combined attitude is hard to combat in a semester course, when the student is one of many sitting out there in a semester class. As well, when they get to college, most students have not encountered the straight-up lecture format before, and it is simply foreign. As the PowerPoint points out, the students are encountering a different form of education for the first time, and they are being asked to adapt to it. However, our current educational structure is so student-focused that the students are not expected to adapt anymore. They should be catered to completely and not asked to leave their comfort zone. When the students encounter the lecture format for the first time in college, they have gone through a life of having their own educational styles catered to over and over, and so their reaction to the lecture is what you would expect. They want what they want, not what we want. What is interesting about this is that I will repeatedly stand up for the right of myself and fellow instructors to grade differently (usually harder) and assess differently, but I am willing to explore different methods of content delivery because the students aren’t responding. I wonder why this is. I have made my own comments here about the lecture format, and I guess that’s it. I do agree that the lecture format is broken, so I have much more tolerance for trying something new.

Of course, what all of this leads into is the bigger question of what college is for. A couple of articles have passed through my Evernote on this topic as well recently. It always helps when the current presidential candidates are talking about it, as that leads to a number of related articles scattered throughout the news sphere. This one from The Washington Post tries to address this broad issue. I have been reading Michelle Singletary’s commentary on personal finance for a while, so I would have read this one even without the educational focus. She sets up the standard two sides of education here, asking, “Is college a time for young adults to just enrich their minds, or should students use that time to concentrate on a major that will prepare them for a career?” She comes solidly down on the second motivation, pretty much dismissing the idea that college should be a time to take whatever classes you want, get whatever degree you want, and just explore. Her point is primarily financial, which makes sense as she is a financial correspondent. She believes that the financial cost of education these days means that students do not have the ability to learn for the sake of learning and need to be focused on what they can get for their education. She does not completely dismiss the idea of education for education’s sake, but she definitely comes down on the side of a practical education. I can’t say I disagree, but I certainly did the opposite. I don’t think I ever got a practical degree, and I feel lucky to have looked for a job and gotten one with my MA in History just before the recent financial collapse. My wife is just finishing up a BA in Art History, and we are currently trying to figure out what to do with that. So, I can understand. It is also at the root of why so many of my students ask me what they have to take history, as they see no practical use for it.

I just have to note this article from The Washington Post as well. It is from the Class Struggle blog on their site, and it gives a nice historical look at the idea of college. As Jay Matthews notes, “The outpouring of college student support after World War II fueled the unprecedented surge of the U.S. economy and its education system. This would be a good time to remember that before we start slipping back.” He notes the challenges facing the idea of college education all around, with Obama pushing more students to enter college, while Santorum is saying we should not. Matthews points out that we see a similar discrediting of education for all that was also seen just before the big push from the GI Bill. He warns us to remember that the benefits of education always seem to vastly outweigh the cost. I am never explicit about this when I teach my students directly. I do, however, always try to talk about the idea of education to my students and to place the education they are getting into a broader context for them. I hope that I do that reasonably well, but I know I could do more. I wonder at what level I need to be doing something like this, talking more about college in the historical sense. I know that the students generally don’t get much direct discussion of the value of college, so we would probably do well to talk ourselves up.

I’m going to close here, as the next article I want to talk about probably needs its own post. Just as a preview, this is the article I want to discuss in some detail. Your homework – read it ahead. OK, just kidding, but it is quite interesting.

Thoughts on Education – 3/11/2012 – What is broken in higher education?

I’ve taken some time off as we begin Spring Break here to get some of my own stuff done. We are doing a big clean out around the apartment, as we are probably going to move out of out apartment when our lease is up, and it would be nice to move a lot less stuff. I also sat down to start our taxes this weekend. Other than that, I’ve been trying to do “other” things, such as catching up on magazine/free reading, going through paperwork, and such things like that.

On my plate also is catching up on some of the articles I’ve been saving up. I’m trying to group them into themes, and today’s theme is articles that talk about what’s wrong with higher education today. I’m going to hold off on my own opinion here to open this post, as that will come out as we move along here.

The first article I came across is this one from the Chronicle of Higher Education. At its center is a YouTube video that talks about why students think that the lecture is a failing model for education. Three big points that come out of it, I think:

- First, they talk about lectures being boring, especially those where the professor simply reads off of the PowerPoint. This is undeniably true, and not just for students. I have been to enough conferences and presentations where this same thing was done to have experienced it myself many times. Solution? Well, we certainly could use some training for how to teach/lecture. Also, professors just need to care more. If that’s what they are doing, then it’s hard to call that really teaching. I imagine, however, that a lot of this is exaggeration on the part of students as well, as I know there are many students who would be dissatisfied/bored with anything that they were told they had to do, which would include listen to a lecture.

- Second, a comment that resonates with me is the one about attention spans and the 90-minute class. While we don’t have 90-minute classes at my community college, we certainly have mostly 75-minute classes. When the average human attention span is 20-25 minutes at the outside, we are asking even the best and most dedicated students to do something unreasonable if we expect them to sit and pay attention to a lecture for 75 minutes at a time. Yet, I do that very thing every day I’m in class.

- Third, and really the comment that stood out to me the most, one students said that they are told over and over to think outside the box, yet the ones who never seem to innovate are their own professors in their teaching styles. Yup. Can’t say anything more than that is spot on.

A second interesting article also addresses these concerns. In “Why School Should be Funnier,” Mark Phillips discusses the uses of humor in the classroom. I think that we do too often take the view that classes and college are serious, important things. As he says in the article, he’s not talking about throwing in a few jokes but about really seeing the absurdity of the situation we are put in. I address this regularly with my class, as I am very open about the failures of the lecture model and how the fact that they are expected to sit here and pay attention for all this time through the semester is, to a certain extent, absurd. My students (I hope!) appreciate it when I give the sly asides, the knowing winks, the “real reason you need to know this,” and all of the other things that I try to do to keep them engaged and going in a format that encourages torpor and boredom.

A third article focuses on the problems of who is driving educational reform. In this case, the experts are pulling us forward to the future. Educational reformers rely on educational experts to tell them what they should do to fix things. Usually, these experts are located outside of schools, connected with specific political ideas, and intent on fixing one part of the system at a time. In each of these cases, we end up with a failure of reform. I have not been asked much about what I think works or not, that’s for sure. In fact, the one group that usually does ask me what works or not are the textbook publishers. I hear from multiple publishers all the time who want me to tell them what is working and what doesn’t. Yet, as you move up the chain of administration or outside of my college completely, I have yet to have any input on the reforms coming down to me. It does always blow my mind every time I see the next thing coming through, and I have to wonder who thought that up. Perhaps we need a revolution from below to fix things.

To close today (yeah, I know, not a long one today, but I am on vacation . . .) is an article about the path of college from The Huffington Post. In it, the author brings together multiple different studies to talk about something very important when considering what is broken in higher education. At the heart of it, we still have an assumption that college works as a straight line, where you graduate from high school, pick a college, go to it, and graduate in four years. Even at a community college, we look at that same thing as the norm, with just the detour of a community college first. I must admit, that is exactly what I assume still as well, despite the evidence in front of my face every day. The reality is that students start, stop, transfer around, switch degrees, leave for 15 years, have kids, hold multiple jobs, get sick, take care of sick family members, join the military, drop out, etc. To shove everyone into that little box of four-year completers is just stupid, when you get right down to it. And, our funding at the college level is dependent on that completely. We fail a student if we can’t get them out in 2 years for community college and 4 years for college. Yet, how many people really do that? How many want to do that? Our funding levels depend on a myth of college completion. Our assumptions about how to teach and advise students works on this myth. Our assumptions on who a student is and what he or she should do in our classes rests on this myth. What is broken is the way we do things. What needs to be fixed is the way we do things. While it is easy to blame the students for that whole list of things that I said up there, the reality is that the students are going to be that no matter what. We have to figure out how to adapt to it. And the people who give us the money to be able to do this had better get it in their heads that just because we can’t say that 100% of our students graduated from our community college in 2 years, that does not mean that we are failing.

Thoughts on Education – 3/9/2012 – Using technology in the classroom

I’m going to try and get back to some of the education issues that have been coming through my Evernote lately. I’ve got quite a backlog over the last couple of weeks while I have been grading, so I should have plenty to write about over the next week or so. Today, I want to concentrate in on the general category of technology in the classroom, as I have been accumulating quite a bit on that recently. Of course, the recent Apple announcements and developments are relevant to this as well.

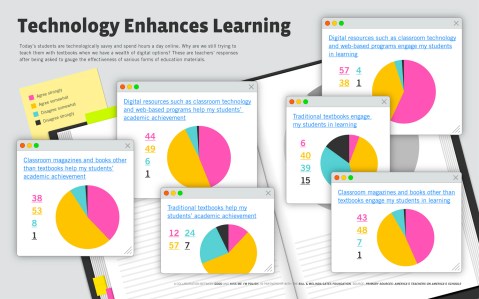

I’m going to start here, with a general article about what teachers think in general about the use of technology. As the article itself says, the results are not particularly surprising, but I will put up the general infographic here, as it illustrates what I think is not too far off from what I see, especially among the younger faculty.

I hope that you can click on that to make it bigger, but the basic message here is that the majority of teachers surveyed thought that technology in the classroom would help both the learning of the students and their engagement with the material. In fact, the two questions that refer back to the older “technology,” namely textbooks, got the lowest Agree responses and the highest Disagree responses. Again, I don’t think there is anything surprising at all about this, but I wanted to start here.

In a similar vein is this article from The Washington Post, which discusses how textbooks are failing to engage our students and help them learn. He notes that textbooks are not effective at engaging students because that is not what sells textbooks. We don’t choose a textbook (me included) because I think it is going to be some sort of magical panacea to solve all of the problems for my students. Instead, at least in history, we look at them primarily in terms of coverage. Which textbook covers the material we want to cover is more important than which textbook students will like. In fact, I have often found that if you talk to a group of instructors about choosing textbooks, the textbook that is most likely to be appealing to students is often dismissed out of hand as not being what works for us as instructors. So, there is a fundamental disconnect there. My feeling about this is echoed in the article as well, where one teacher is quoted as saying, “Even when adoption committees include content specialists, these people typically evaluate the accuracy of the content, rather than whether the instructional strategies are effective.” In fact, the author quotes another educational administrator, who noted, “The educational community was quick to respond to the (legitimate) criticism of textbooks but quicker still to adopt their horrific replacements: excessive use of lecture, worksheets, movies, poster making, and pointless group work.” We are flailing around as far as I can see. I feel like that myself, where I am just trying so many different things all the time without ever knowing what I’m doing. That’s why I’m doing this, so that instead of trying new things at random, I am trying to plan things out. Anyway, there’s a lot more to this article, and I do recommend it as very interesting reading when we think about how the old technology options are failing us.

And, when I read this article from the Chronicle, I saw myself and how I use technology a lot of times. Unfortunately, I don’t mean that in a good way. As it says, in online courses, especially at the community college level, “the professors are relying on static course materials that aren’t likely to motivate students or encourage them to interact with each other.” While I get a lot of compliments from students about the way my course is organized, I know that I use few real tools, and I certainly do not effectively encourage interaction in my classes. The article goes on to talk about a study where the results came from. That study concluded: “It found that most professors relied on text-based assignments and materials. In the instances when professors did decide to use interactive tools like online video, many of those technologies were not connected to learning objectives, the study found.” I certainly would say mine fits this completely. My course, is completely text-based. There is little to no video or interaction in my own materials. I have adopted some from McGraw-Hill that I use in conjunction with my textbook, but that is actually in a completely separate classroom from my own in Moodle. While the article does note that technology is again not a panacea to solve all of these problems, I think that in the online environment, a failure to be innovative in technology will cause the students to treat the course as a chore to get through. Of course, I may just be thinking some fairy-tale thoughts here that a student could really feel completely engaged by an online course, but I think I could do better.

As we think about the future of technology in the classroom, there are a lot of directions it could go. I’ve been exploring some of those in this blog as I have gone on here. I am trying to keep current on what’s going on out there, and trying to see what ideas might work for me. This article from Mind/Shift talks about the future of technology in the classroom. The article considers the near, medium, and long term forecast for technology. In the near term they consider mobile apps and tablet computing as the center piece of where we are going. We certainly are thinking about that at my community college. The faculty work group that I’m on has been given iPads to explore and the task of finding apps that can be used in the classroom to enhance learning. As well, we will be buying classroom sets of iPads to use. So, nothing new there based on what I have seen. The mid term is going to be gamification and the use of data to influence education. I have also been exploring gamification in this blog, so I guess I’m right on top of that topic as well. As to the use of data, if the big assessment push we all seem to be on is any indication, I think we’re already on this path. I don’t know how far it will go, but it is certainly a trend that we are involved in. The longer term is going to include gesture-based computing and increasingly ubiquitous connections to everything. I certainly agree that those are both technologies that could come into play. What is interesting about the article though is that the so-called future of technology in education includes little that I’m not already engaged with. I guess that means that instead of looking to these things to come out in the future, I need to figure out how to use them now and just get on with it.

So, where am I going with this. Still thinking, but moving along. I want to incorporate technology, and I want relevant change. I don’t want change for the sake of change, as I feel like that is what I have been doing for quite a while here. I think that more is needed, which is why I keep working on this blog. I need real change that comes with solid thought and evidence behind it. It will still be an experiment, of course, but I would like it to be an experiment that is directed in a productive manner. So, I shall keep thinking and planning. It’s hard to do more in the middle of the semester. Let me know what you think? Those of you who teach, what are you thinking of doing? Are you looking to change something? Those of you who do not teach, what would you like to see?